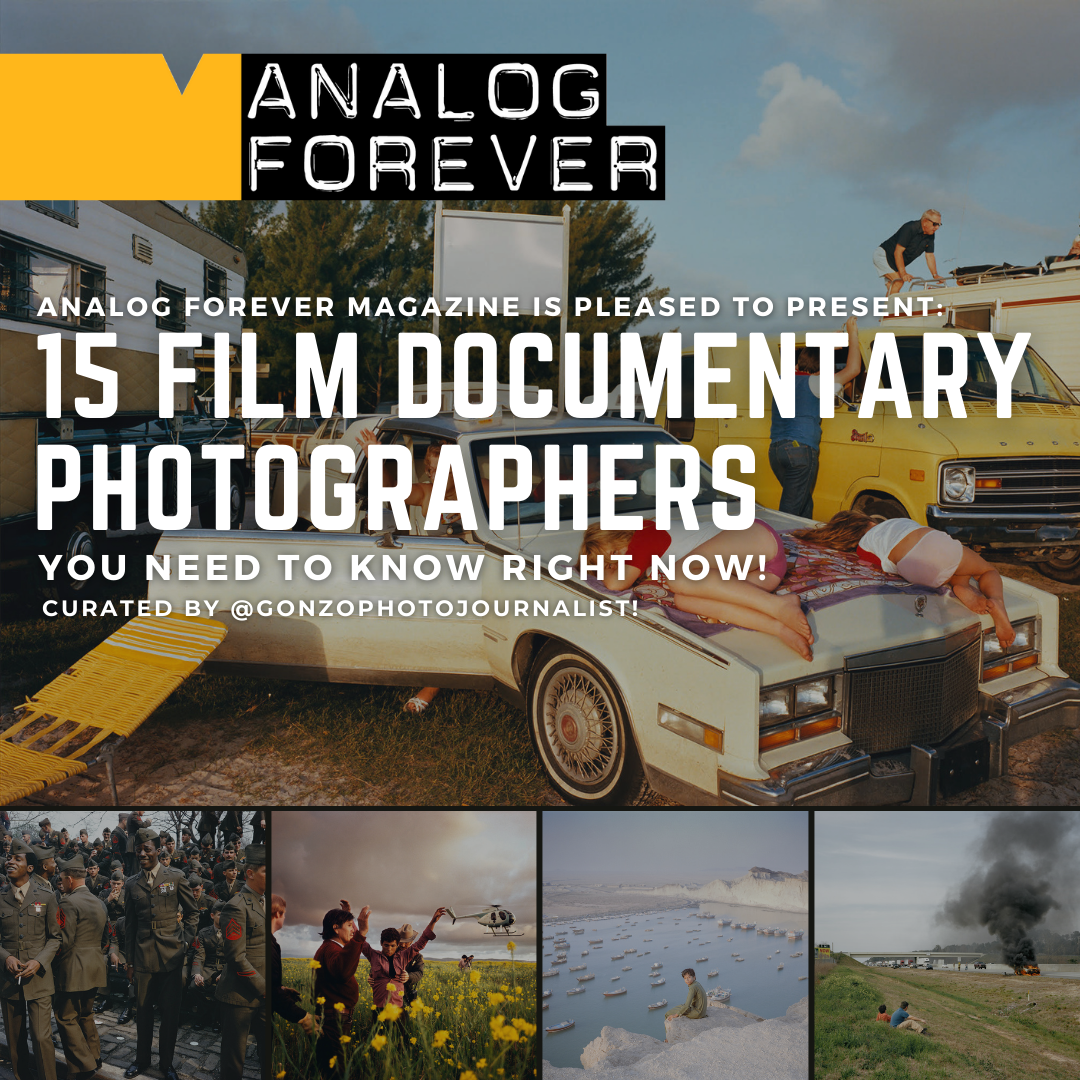

15 Film Documentary Photographers You Need to Know!

Not long after the invention of several different viable processes for creating permanent or semi-permanent photographs, a debate began over whether or not these renderings should be thought of as dispassionate documents or a means of artistic expression. This debate has continued in fits and starts through the present. However, it has not been particularly fruitful, as any lens-based photographic process is just a tool that produces a representation of whatever was in front of the lens at the time of exposure. The first book of camera-derived photographs ever published, The Pencil of Nature, by Henry Fox Talbot, in1844, not only addresses the implications of photography as an artistic medium and as an objective document, but contains a variety of plates that demonstrate it was capable of both. It is no surprise that photography was used from its earliest iterations to create both art and documents, with the primary delineation between the two being the intention of the person creating the photographs.

While both categorization and classification can be helpful approaches to breaking down the world of phenomena and concepts into pieces digestible to the human mind, there are rarely distinct boundaries between categories. Documentary is a category of photographic practice that likely has the bluriest boundaries. Using a process so capable of visual verisimilitude to engage with themes as tangled and complex as war, poverty, oppression, suffering, crime, and all manner of messy human interactions, sets the stage for a tense review of all photographs created thereof. The images that can arguably sit under the umbrella of documentary range from the conflict photojournalism of James Nachtwey to the intimate auto-ethnographic images of Nan Goldin. However, the societal implications of these images vary greatly. The former approach can be held up as veracious evidence by journalistic outlets and even in legal proceedings, the latter approach is true insofar as it artistically illustrates a subjective personal narrative. The deeper questions raised by documentary photographic practice might include: Do photographs function as objective descriptions about phenomenological events or as visual metaphors that elucidate societal and human truths? Does the context in which a photograph was taken have relevance to how it should or might be interpreted by a viewer? Is there an imbalanced power dynamic between the photographer and the subject of a photograph? Does this matter, and if so, how?

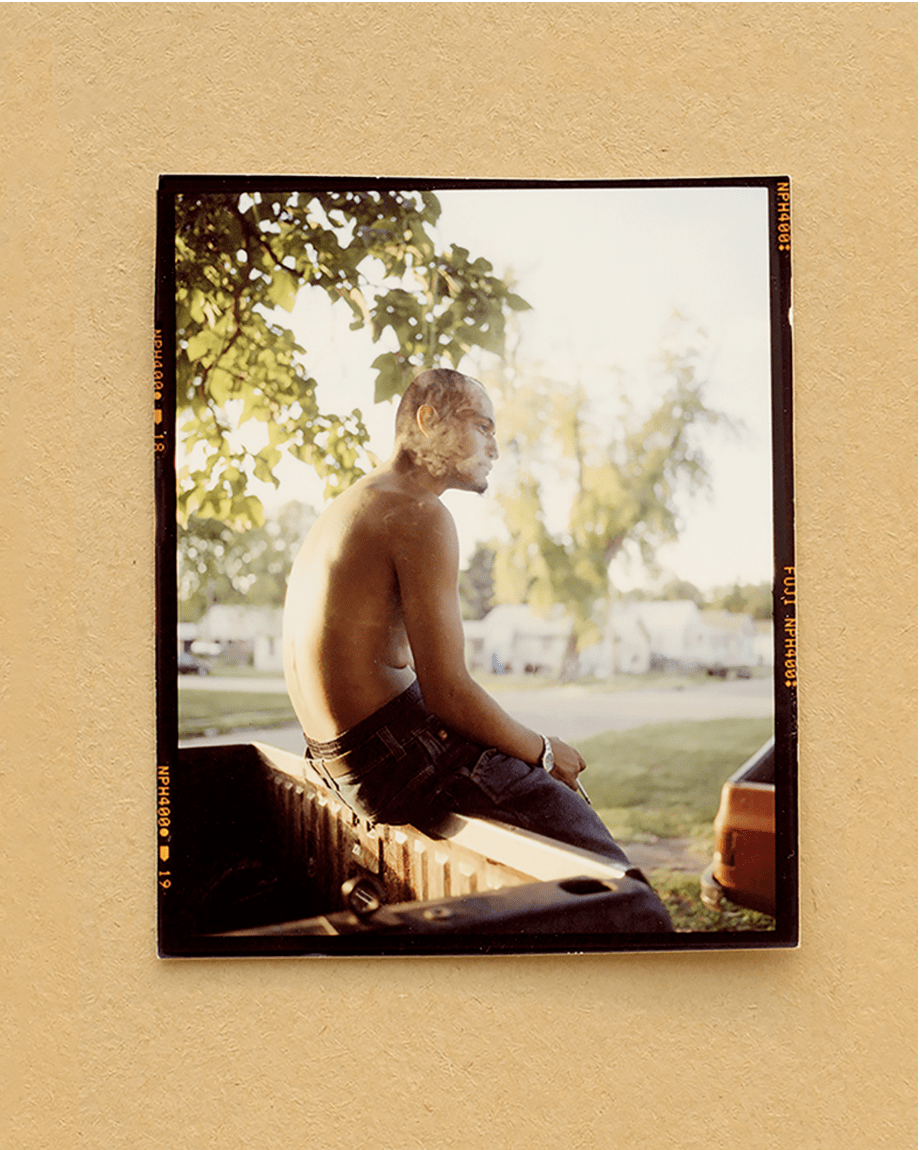

“Cocoa Beach I, Florida 1983” by Mitch Epstein | 6x9 Palm Press, Kodak 400 Negative Film

These questions get at the heart of empistemological and ethical concerns in photography. Artists, critics, historians, and many others concerned with photography have been asking these types of questions since the medium’s earliest days, but the question that might be most fascinating and productive is one that does not have one answer: What can photographs tell us (about the world, our time, each other, ourselves)? The answer is always changing and expanding, depending on the time and culture in which images are produced and by the particularities of the photographer taking the pictures. Art more generally has always had the quality of a metaphysical mirror, reflecting back to the viewer both a sense of the artist who created it and the context in which it was created. Photography oftentimes brings the image in this mirror into uncannily sharp relief, generating a disquieting relationship between fact and truth, the dual intimacy and dissociation of the camera’s gaze, and the paradox of time appearing to be made still while never being able to experience such a state of perception firsthand.

With this conceptual groundwork laid, what can documentary photography tell us? The associations of the genre with photojournalism and monumental projects such as the U.S. government-sponsored Farm Security Administration collection of 175,000+ surviving negatives have created a lingering perception that documentary photography is a fact-oriented venture. However, even the extensive scope of the RA-FSA project does not detail every aspect of life in America and its territories during the time it was produced. And how useful is such a large collection of images in communicating a comprehensible narrative of its subject matter? Searching for factual truth through documentary photography brings to mind the fable of Borges’ map, in that an attempt to create an absolutely comprehensive description of a thing results in a description that is just as expansive and complex as the thing itself. In this light, the most powerful and meaningful approaches to documentary photography do not concern themselves with attempts at a comprehensive or objective photographic description, rather they engage subjects or themes through human qualities such as uncertainty, compassion, curiosity, and beauty--that is, things humans use art to address.

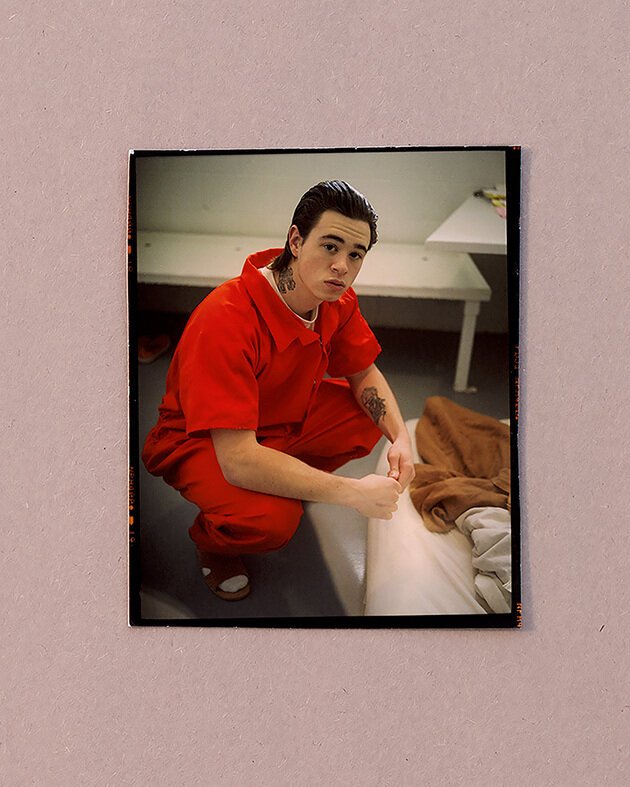

“Elkview, West Virginia, 2016” by Joshua Dudley Greer | Toyo 4x5 Field Camera, Kodak Portra 400

Coincidentally, when I was approached to write this article and curate this collection of documentary photographers using analog processes, a large exhibition opened and a new book was published exploring the vanguard of this genre. The show is titled But Still, It Turns: Recent Photography from the World, at the International Center of Photography (ICP), was on display from February through August 2021, and the book is titled simply But Still, It Turns, published by MACK. Nine photographers are featured in the exhibition, including well-known names such as Gregory Halpern, RaMell Ross, Vanessa Winship, to name a few. Both the exhibition and book are curated by photographer Paul Graham, and his essay Belonging Particles functions as an introduction to both. In his essay, Graham posits that “[t]his photography is post documentary, released from restrictive briefs and reductive narrative within which places and people are all too conveniently shuffled.”

Graham should be applauded for taking issue with the most influential institutions of art prioritizing more conceptual studio-based and/or digitally-manipulated images as the vanguard of fine art photography at the expense of promoting the work of those making images in the documentary genre. However, the thrust of his essay-manifesto that documentary photographers are doing anything particularly new is ultimately overstated and strained. One could look all the way back to Eugène Atget to find images with a variety of subject matter, vitality, and visual lyricism present in contemporary documentary photography--especially considering that Atget was shooting glass plate negatives nearly 8x10 inches in size. The throughline of earlier generations of documentary photographers to contemporary practitioners becomes even clearer when the work of Roy DeCarava, Robert Frank, William Eggleston, and many other twentieth-century photographers is considered.

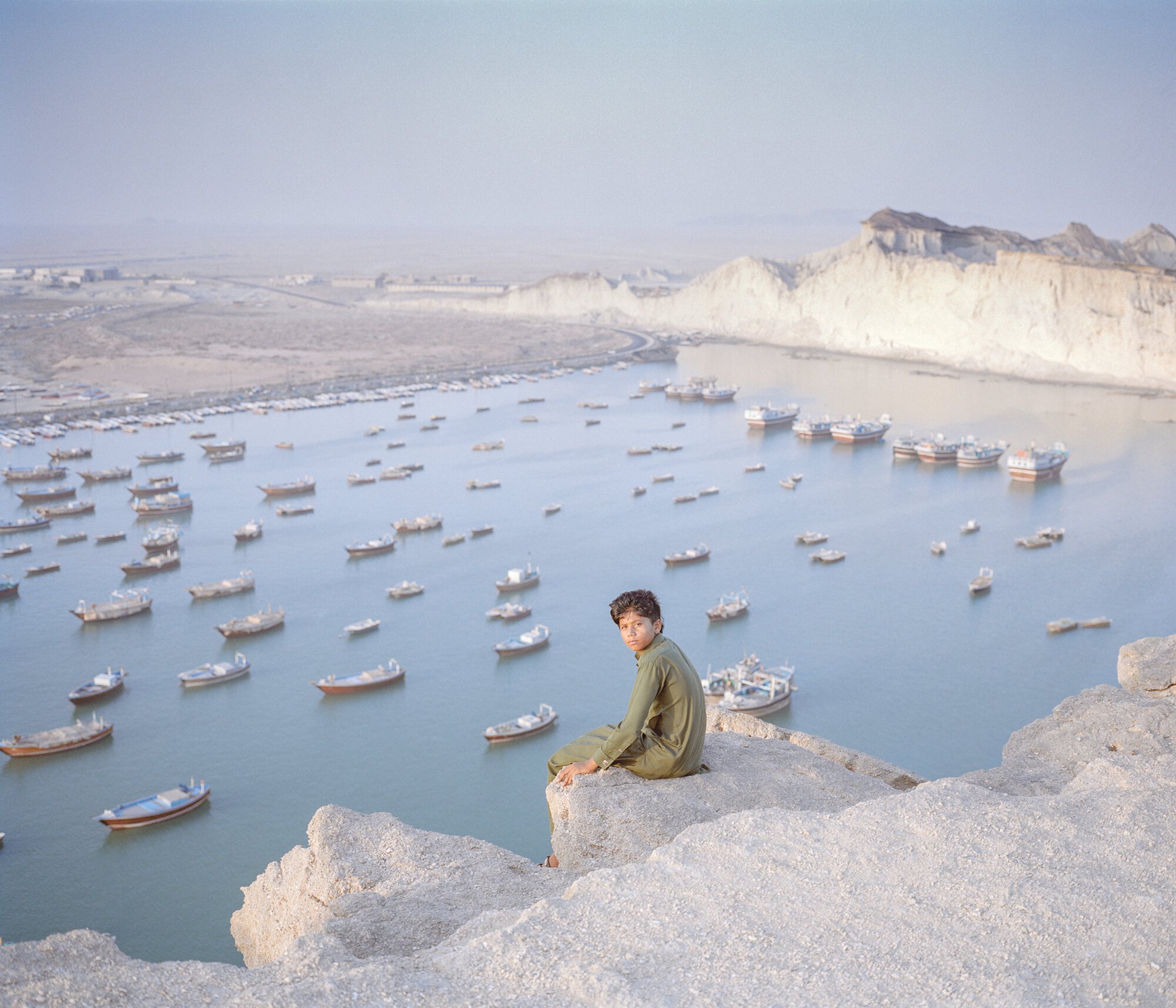

"San Ysidro, California, USA, 1979" by Alex Webb | Leica Rangefinder, Kodachrome 64 Film

A strong argument could be made that But Still, It Turns is the contemporary iteration of the famous 1967 MoMA exhibition, New Documents, featuring photographs by Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, and Diane Arbus, curated by John Szarkowski. And at the risk of putting too fine a point on the matter, Graham’s proclamation that the contemporary vanguard of documentary photographers are outstanding because, “...there is no singular story is the story. These artists tell us that all is in play, that everything matters.” reads like a familiar echoing of Szarkowski’s wall label for New Documents, “[these photographers] like the real world in spite of its terrors as the source of all wonder and fascination and value--no less precious for being irrational… What they hold in common is the belief that the commonplace is really worth looking at and the courage to look at it with a minimum of theorizing.”

To be fair, Graham directly cites many of the photographers just mentioned, but brushes past any deep engagement that distinguishes their work and practice from what contemporary documentary photographers are doing. Above all, more questions that have always lingered with me come to mind when considering the desire for novelty and individual distinction: why do artists, and individuals in Western society more generally, care so much about doing something new or distinct? Does this urge belie some sort of existential terror that our lives and efforts do not amount to anything significant in the broader scope of human history, that we are atomized islands of human experience and not all part of a common humanity? Why should anyone feel angst or fault for contributing to an extant project, especially something that can be as insightful, moving, and beautiful as documenting the intricacies and varieties of human experience through the medium of photography?

Ultimately, all photographers trying to communicate the beauty they see in the world and other people should be able to find a sense of delight and contentment in contributing to a sweeping, ongoing project to honor the diversity of human experience, to find and transcribe a visual poetry of our world. The following list of photographers presents us with perspectives from around the world, representing a variety of cultural backgrounds, yet all are united by an earnest intention to use photography to communicate what they find meaningful and human in the world around them. Some create work that spans political borders and continental divides, others engage specific geographies or cultural communities. All use film cameras, and some use a fully analog process to capture and print their images. Analog capture and printing has experienced a revival since the adoption of digital photography by commercial industries. The near total obsolescence of film photography as a commercial process has imbued it with an aura that lends itself to artistic expression instead of an industrial tool. Unlike digital photography or any other form of artistic production, the photochemical process has the seemingly magical power to manifest a physical artifact directly from the stream of photons that ceaselessly bombard and project off all that can be seen.

- Joseph Webb

15 Film Documentary Photographers You Need to Know Right Now!

Artist: Missy Prince | Location: Portland, Oregon

Links: Website | Instagram

“I’m not really trying to tell a story but I am trying to hint at something. A photo can work like a sentence that makes you see beyond what is written. It is literal and fantasy-inducing at the same time.” - Missy Prince

Like many photographers with an exceptional ability to communicate an ethos of place through images, Missy Prince has spent time immersed in different geographical contexts. Growing up on the Gulf Coast of Mississippi and moving to Portland, Oregon, just after high school, Price has also dedicated long stretches to exploring the American West, especially desert landscapes. Her approach to photography is refreshingly straightforward and unpretentious: “a curiosity about the world and the way people live,” “being out in the world and remaining open to anything,” a recognition of “the potential of the every day.”

Prince’s photography kit is rather spartan, shooting primarily with a Mamiya 7, an Olympus XA, and occasionally instant film with a Polaroid SLR 680. She is an avid color darkroom printer, stating that, “having a physical print is such a big part of my drive to photograph. I am not totally satisfied until the print is made.” While she does use a hybrid digital process for some of her images, she has lamented the loss of her local darkroom in interviews and regularly drives several hours north to Evergreen State College to print in its darkroom.

Prince published her first book of photographs in 2009, Now It’s Dark, a collection of 68 color Polaroid prints that fully leverage the low fidelity, painterly quality of the process to dreamily illustrate everyday scenes of the Northwest. For her second book, Why Don’t You Come Home (2016), Prince returns 35mm and 6x7 color images of landscapes, interiors, and portraits from her home state of Mississippi that simultaneously feel matter-of-fact and suggestive of something beyond what is rendered. A similarly ambivalent and elliptical sense is present in her latest publication, River’s Edge (2019), which is made up entirely of 6x7 color photographs that strike a delicate balance between the stark and lush beauty of the Northwest.

Artist: Gregory Halpern | Location: United States

Links: Website | Instagram

Gregory Halpern creates photographs that help define an early 21st-century gothic aesthetic, making images of a world that feels unflinchingly real and eerily ethereal simultaneously. Through a sort of artistic alchemy, he combines seeming opposites of dispassionate distance and empathetic compassion into something lyrical, meditative, and, ultimately, difficult to apprehend.

In 2003, he published his first major series of images, Harvard Works Because We Do, as what many would recognize as a modernist photo documentary project, containing many composed portraits and contextualizing text that drove a clear narrative and moral framework. Halpern didn’t publish another series until 2009 when Omaha Sketchbook was released as humble spiral-bound laserjet printing in an edition of just 35. Omaha Sketchbook and every subsequent series undertaken by Halpern stand in stark contrast to Harvard Works Because We Do through his embrace of an oblique, ambivalent moral sense rendered as richly colored images that document the fringes of American society, and most recently, French Caribbean culture.

In 2019, an expanded edition of Omaha Sketchbook was published by MACK, and Halpern has released 3 other visionary series, A (2011), Zzyzx (2016), Let the Sun Beheaded Be (2020), along with notable collaborative projects. Halpern works extensively in 6x7 medium format, using the Mamiya 7 and Pentax 67 systems, and 4x5 shooting color negative film that he prints himself as optically enlarged chromogenic prints.

Artist: Joshua Dudley Greer | Location: Atlanta, Georgia

Links: Website | Instagram

Joshua Dudley Greer's documentary photography practice follows in the same tradition of continent-wide roaming of the American landscape established by luminaries such as Stephen Shore and Joel Sternfeld. Most well known for his 2020 monograph, Somewhere Along the Line, it comes as no surprise that Greer cites Sternfeld’s American Prospects as a book that greatly influenced him. Throughout Greer’s three major series (American Histories, 2005-2009; Point Pleasant, 2009-2012; Somewhere Along the Line, 2011-17) people are present in the compositions, but the images are definitely not portraits. Rather, people are situated within landscapes in a manner that consistently evokes an impression of a larger narrative at work. However, this does not keep his images from feeling empty of human concerns and emotion, as many of his images present “unforeseen moments of humor, pathos, and humanity.”

The similarities between Greer, Shore, and Sternfeld are not limited to grand explorations of America and attempts at unifying its vast geographic and social diversity through photographs, but also in terms of his technical process. Like the iconic mid-late 20th century straight photographers just mentioned, Greer shoots exclusively large format color film--mostly 4x5, while some images from Somewhere Along the Line were also shot on 8x10.

Artist: Saleem Ahmed | Location: United States

Links: Website | Instagram

“I am constantly searching for peace and quiet in a world that is often too loud.” - Saleem Ahmed

Raised in Connecticut, but now living and teaching in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Saleem Ahmed has deep family roots in Udaipur, India, and the Indian Musilim community. Ahmed has made frequent trips to visit family in India and many of his photography series are dedicated to exploring the people and landscape in and around Udaipur. However, Ahmed has also undertaken documentary series in Philadelphia, Turkey, and La Paz, Bolivia. Though his photography has captured scenes from around the world, his treatment of seemingly unconnected places are united by a subtle, harmonious photographic vision that is deeply contemplative, subtle and poetic. He has written about his approach to photography as relating to the Japanese aesthetic principle of wabi-sabi, which can be roughly summarized as discovering beauty in imperfection, with his own personal interest in the beautiful imperfections that are introduced by human activity.

Most of Ahmed’s photographs are captured with color film in 6x7 format with cameras such as the Plaubel Makina 67 and Fujifilm 667. Some of his noteworthy publications include Tasveer (2014), Peace In The Valley (2017), Rani Road (2019), and LOST, Philadelphia (2019). His love of photography was combined with his passion for education in 2010, resulting in Vista Oculta, a program that introduces children in La Paz, Bolivia, to medium photography. Ahmed is currently an assistant professor of journalism at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Artist: Dan Wood | Location: United Kingdom

Links: Website | Instagram

Dan Wood has spent a lifetime engaged with the landscape and people of his native Wales. First becoming interested in photography in the 1990s as a way to document skateboarding, mostly in 35mm format on black and white film. His approach to photography and personal life underwent substantial change in 2013 when he began shooting color film with a medium format SLR and his wife became pregnant with their first child: “It felt so refreshing and new to be using the Hasselblad and colour film, but I was also contemplating my family’s destiny at the same time.”

The result of this shift in photographic process and personal perspective was Wood’s first monograph, Suicide Machine (2016) and the beginning a deeply engaged documentary exploration of his hometown, Bridgend. Suicide Machine was followed by Gap In The Hedge (2018) and the unofficial “Bridgend Trilogy” was completed in 2021 with the publication of Black Was the River, You See. Wood’s images document contemporary Welsh life with an intimate, sometimes delicate realism. They demonstrate a dedication to understanding the community to which one belongs and ponder over what the future holds for people when forces beyond their control make a once stable way of life precarious.

Since that time, he has quickly garnered attention and has been publishing collections of his photographs at a blistering pace. He was awarded the Portrait of Britain prize by the British Journal of Photography in 2018, released five monographs from 2016 to 2021, and his photographs were acquired by institutions such as the Martin Parr Foundation, National Museum of Wales, and the International Center of Photography, among others.

Artist: Kyler Zeleny | Location: Canada

Links: Website | Instagram

Growing up on a farm in Alberta, Kyler Zeleny is the preeminent documentarian of the vast prairie landscape of central Canada. Although only in his early 30s, Zeleny has a prolific and wide-ranging number of projects. He has published two monographs of original photographs, Out West (2014) and Crown Ditch & The Prairie Castle (2020), four additional long-term projects outlined on his website, and curates the vast collection of instant film photographs Found Polaroids (comprised of over 6000 found images, an excerpt of which was published as a book in 2017).

While his numerous short-term and long-term projects reflect a varied interest in different subjects and approaches to photography, Zeleny’s medium format color photographs of rural Canada, as presented in Out West and Crown Ditch & The Prairie Castle, stand out in their geographic breadth and deep engagement with subjects. In a statement on his website, Zeleny writes that much of his work stems from, “a fascination for elements of the past and pondering the future.” This sentiment is beautifully rendered in Crown Ditch & Prairie Castle, which strikes a graceful balance between entertaining nostalgia and challenging it, presenting landscapes and portraits of archetypal rural scenes and people that feel both frozen in the recent past and threatened by the encroaching future.

Keleny uses a variety of film cameras and films--35mm, medium format, instant film, black and white, and color. For his long-term projects, he has deployed a single type of medium format for each: a Yashica 124G for Out West and a Pentax 67 for Crown Ditch & Prairie Castle.

Artist: Hashem Shakeri | Location: Iran

Links: Website | Instagram

Only in his early 30s, Iranian photographer Hashem Shakeri has produced perhaps two of the most artful, moving, and socially conscious series of photographs in the country’s history. It is his stated concern with a “psychological investigation of human relationships” and using photography to “provide a universal narrative with a personal insight” that elevates his imagery beyond photojournalism into the realm of poetic visual art.

Shakeri’s images have a distinctly soft-hued lightness that is achieved primarily through his intentional overexposure of color negative film. This signature aesthetic is further refined by his use of a Mamiya 7 rangefinder camera that tends to render scenes with a clarity and delicateness not achieved with smaller formats. This style, beautiful in its own right, when deployed to illustrate the hardship and malaise Shakeri addresses in his series, creates a dreamily poignant atmosphere for viewers to fall into.

The two major projects Shakeri has completed to date, An Elegy for the Death of Hamun (2018) and Cast Out of Heaven (ongoing), both explore the troubled relationship between humans and their environment. The images in An Elegy for the Death of Hamun truly feel like a visual funerary hymn or rite dedicated to people and land around Hamun Lake as it dries into nothingness in Iran’s far eastern Sistan region. Cast Out of Heaven documents the surreal landscape of massive public housing projects built on the outskirts of Tehran and their inhabitants as they cope with a new, disconnected way of life. Shakeri states that these projects are the first two installments in a trilogy of work, the third installment of which will surely not disappoint.

Artist: Mitch Epstein | Location: United States

Links: Website | Instagram

“Photography remains a tool with which I form and sharpen my response to the world around me. Anything and everything is photographable in an infinite number of ways. That excites me.”

Mitch Epstein is a member of the transformational generation of mostly American photographers who seriously engaged with and challenged the conventions of modernist photography of the first half of the twentieth century. Beginning in 1972, Epstein moved to New York to attend Cooper Union, where he studied under Garry Winogrand. Like other luminary photographers of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Epstein pursued a more individualistic, subjective values system in his artwork and did so with color film: “I started to work in color, which was a radical, and some thought foolish, move in 1973. Color photography was not yet a medium for serious photography...”

While greatly influenced by the curatorial practice and critical ideas of John Szarkowski, much of Epstein’s work channels more definite themes and project structures, differing from the practice of the more radically subjective, intuitive photographic approach of contemporaries such as Winogrand or Eggleston. Whether it be his trilogy exploring the “meaning and look of American-ness”--The City (2002), Family Business (2003), and American Power (2009)--or his projects exploring cultures outside America--In Pursuit of India (1987), Vietnam: A Book of Changes (1997), Berlin (2011)--Epstein has always approached his projects with “rules” and a willingness to “break, or at least bend, those rules so as to subvert my own intentions and let the work breathe; let it hold multiple and mysterious dimensions.”

While many of his early projects were shot with 35mm cameras, he is best known for his extensive use of 8x10 format. Whether shot in black and white or in color, on small or large format cameras, Epstein’s vision has a consistency and harmony that spans his entire career. His 2019 publication, Sunshine Hotel, is the first collection of his work that was not project specific, spans over fifty years of his work yet feels fresh, cohesive, and demonstrates an artistic clarity that is inspirational.

Artist: Greg Girard | Location: Canada

Links: Website | Instagram

“Sometimes appearances don’t always align with what you know or suspect to be true. Photography seems able to show the surface and peel it back at the same time.” - Greg Girad

Canadian photographer Greg Girard has always maintained a deep curiosity about the world and the importance of firsthand experience thereof. Many photographers find the camera to be a sort of physical extension of the psychological desire to observe intensely and deliberately, and that seems to be the relationship that Girard has had with the medium from an early age. Starting in his late teens, Girard began taking frequent journeys from suburban Vancouver to photograph the grittier downtown and waterfront of the then port city. Over the course of 10 years, Girard amassed a considerable collection of 35mm color photographs that remained unpublished until 2017, with the release of Under Vancouver 1972–1982. A substantial proportion of the collection consists of long-exposure nighttime scenes of artificially lit subjects that anticipate both his later work throughout Asia and the practice of photographers such Todd Hido.

Following his desire to explore the broader world, especially East Asia, Girard traveled by ocean freighter from San Francisco to Hong Kong in 1974. This was the beginning of a nearly 30-year period of living in Japan, China, and Hong Kong, working mostly as a freelance commercial photographer for magazine publications. However, in 1985, Girard, along with photographic partner Ian Lambot, began a 5-year-long survey of Hong Kong’s mysterious and infamous Kowloon Walled City. This project resulted in the 1993 publication City of Darkness, a truly unique survey of the people and architecture of one of the most interesting urban environments in modern history.

The completion of City of Darkness also marked a turn for Girard, moving away from commercial assignments and a photojournalistic style, toward a concentration on personal projects and his own interests. His subsequent series show a greater use of medium format (specifically the Mamiya 7 system), a continued use of vivid slide films and exploration of night photography, and deeper engagement with location specific themes throughout East Asia--from the post WWII America Japan traction around the US military base in Okinawa in Hotel Okinawa, 2017, to the dramatic pace and cost of urban development in Phantom Shanghai, 2007. As a Westerner who spent over half of his life photographing and living throughout Asia, Girard challenges us to think about what defines one as an outsider or how entangled with a culture one has to be to have something significant to say about it. He puts it simply but his perspective is an insightful one: “...the guiding thing was that the pictures would have to be interesting to people who knew the place and lived there, rather than interesting to the folks back home, as it were.”

Artist: Juan Aballe | Location: Spain

Links: Website | Instagram

“I think of ambiguity and uncertainty as essential virtues of the photographic language that help me better understand myself and other human beings.” - Juan Aballe

Madrid based photographer Juan Aballe is deeply interested in the concepts of nostalgia and hope. Rather than pedling in it with a shallow sentimentalism, he uses photography to thoroughly investigate their implications both materially and psychologically. Aballe describes the photographs in one of his series as “somewhere between reality and my imagination,” which is an articulation that well encapsulates the overall impression of his imagery and the essence of nostalgia and hope.

Since 2011, Aballe has concentrated on two major photography projects, resulting in two beautiful monographs, Country Fictions (2013) and Last Best Hope (2021)--both captured entirely on color negative film with a Mamiya 7 camera. Produced over the course of two years, Country Fictions documents the inhabitants of sparsely populated rural villages throughout Spain. With a desire to create “somewhat dream-like images that had a subtle tension to them,” Aballe presents beautifully subdued images that intertwine the bucolic and the precarious, the idealization of rural life and its manifest reality. His more recent project, Last Best Hope, takes Abelle across the globe to the western United States to document the residents and landscape around Oakland, California. In this work too, Abelle uses photography to create tension between idealization and reality, though this time exploring hope for the future as it is challenged by the conditions of the present.

Artist: Alex Webb | Location: United States

Links: Website | Instagram

“My work is questioning and exploratory. I believe in photographs that convey a certain level of ambiguity, that ask questions rather than provide answers.” - Alex Webb

For over 40 years, Alex Webb has contributed more to the standing of documentary photography than almost any other living photographer. His effortless yet complex compositions and brilliant use of highly saturated color palettes are iconic, bringing to mind strains of the same genius seen in Catier-Bresson and Eggleston, respectively. Traveling extensively throughout Latin America and the Caribbean in the late 20th century, Webb’s photographs do not feel like the world as seen through the eyes of a tourist or interloper. His images embody a sensitivity and humanity that is admirable and gripping, if not aspirational. He has sometimes referred to himself as a street photographer, but that label seems almost too limiting for a photographer that straddles the line between photojournalistic and artistic documentarian more deftly than any other.

Webb’s collection of photobook publications spans over 30 years at this point. The 2011 monograph, The Suffering of Light, is the definitive collection of Webb’s most remarkable images and cements his status as one of the most talented photographers of the last century. He is well known for his use of Kodachrome film and Leica M series 35mm cameras, both of which contributed heavily to the signature look of his photographs.

Artist: Matteo Di Giovanni | Location: Italy

Links: Website | Instagram

“...photography has one crucial thing in common with philosophy: it doesn’t give answers, it generates more questions.” - Matteo Di Giovanni

After reading any text by or interview with Matteo di Giovanni, it comes as no surprise that he studied philosophy before becoming seriously interested in photography. Although the concepts surrounding his photographic practice are often heady and esoteric, he ultimately views photography as a route to poetic and lyrical expression. His aesthetic reflects his contemplative, unhurried process. Setting aside long stretches of time to travel by car and haul along his 4x5 camera, di Giovanni dives deep into his subject landscapes as a means to elicit exemplifications of themes grander than the contents of any one photograph.

Released during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is eerily fitting that the concept underpinning Blue Bar (2020) is “uncertainty.” Some photographers embrace and leverage spontaneity to candid and unexpected imagery, di Giovanni’s approach is antithetical in its calculation, and his photographs exemplify this with their often somber, pensive tone and considered compositions. Blue Bar is the second installment in a trilogy containing images produced from 2013 to 2021. The first installment is titled I wish the world was even (2019) and the third is tentatively titled Traces which is scheduled for publication in late 2022.

Artist: Bryan Schutmaat | Location: United States

Links: Website | Instagram

Bryan Schutmaat gained almost instant recognition and adulation in 2013 with his release of Gray the Mountain Sends. A powerful and concise statement of documentary photography containing only 40 images, all captured on 4x5 color film. Situated in mining communities throughout the American Rockies, the vast landscapes, intensely composed portraits, and somewhat forlorn atmosphere, Schutmaat established the themes with which his photography still investigates and elevates: masculinity, the aftermath of rapid westward expansion and development, rural identity, the relationship between people and landscape, an economic system that leaves many behind.

Schutmaat certainly has a distinct style and approach, consistently polished and considered while never feeling contrived or artificial. He has an uncanny ability to make the ordinary feel monumental and transcendent. This description of his work applies almost conspicuously so to Gray the Mountain Sends, but does so in a surprising way to his second monograph, Good Goddamn (2017), which sees Schutmaat make the switch from color to black and white, and contracts the range of subjects and geography to a single individual depicted on his own property in the last days before going to prison. His latest series, Vessels (2020), expands his scope again. This time, to the desert of the Southwest, eloquently capturing the isolation of the landscape and tentative existence of society’s fringes. He certainly ranks as one of the most visionary photographers documenting America today.

Artist: Nadia Bseiso | Location: Jordan

Links: Website | Instagram

“...The Arab world has always been connected by an invisible umbilical cord. Even if we have manmade borders, whatever happened around us is close to home.” - Nadia Bseiso

Nadia Bseiso possesses a distinctively poignant grasp on the spirit and identity of the greater Arab world that is beautifully illustrated in her color photographs. Based in Amman, Jordan, Bseiso has traveled extensively throughout her home country since 2016 producing photographs for her most well-known project, Infertile Crescent, which has been twice selected by the Arab Documentary Photography Program and, most recently, garnered her a grant from The Aftermath Project. In addition to her personal projects, Bseiso works as a freelance photojournalist, with contributions to The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Telegraph, Zeit Magazine, among others.

Bseiso states that her “projects are driven by curiosity that trigger [sic] research in history, geopolitics and mythology, and later transforming to a visual narrative.” The somewhat academic tone of this statement belies the exquisite balance of straightforward representational clarity and subtle emotional depth present in her imagery. The themes of history, contemporary geopolitics, borders, and natural resources seem to act primarily as a subtextual foundation upon which she spotlights the everyday, personal lives of people as well as the vast, varied landscapes of the region. To date, she has captured imagery for two projects entirely on medium format color film, Infertile Crescent and OilMill, and each combine pictorial elements of water, fire, and figure into series that feel much more like an instance of eerie modern myth or parable than photojournalistic examination of political and environmental tensions.

Artist: Patrick Joust | Location: United States

Links: Website | Instagram

No other photographer has documented contemporary Baltimore more than Patrick Joust. Although he settled in Baltimore in 2002, becoming interested in photography around the same time, it wasn’t until 2007 that his first film images of the city began to be published online. In the past 10 years, Joust’s photography has significantly matured and he has explored many different approaches to photography--night photography, use of colored flash, straight/observational, and street portraiture. His images come in a variety of formats (half-frame, 35mm, medium format), but his color medium format photographs, captured on a Fujifilm 6x9 rangefinder and variety of 6x6 TLR cameras, stands out as some of his most exceptional.

Unlike most photographers, he seems to publish almost every exposure he makes. His Flickr page is an exhaustive archive of over 13,000 images, almost all of them film captures, and it dates back to his earliest images of Baltimore from 2007. Joust’s approach to photography is admirably uncomplicated and humble, describing his relationship with the medium as, “so important to my day to day life that I don’t want it to be defined in terms of whether it’s successful by any traditional measure.” Never working as a commercial photographer or having any formal arts education, and not taking much interest in institutional fine art recognition, he is in some ways a quintessential outsider artist. However, he is not a person living on the fringes of society, as is often associated with the term, instead of describing himself as “a pretty normal guy...I’m married, have a kid, I work as a librarian.”

It seems condescending to describe Joust as a photography enthusiast or hobbyist, as his work, especially landscapes, portraits, and night photographs, are rich with artistic and emotional expression. However, maybe his approach proves that any activity deeply pursued with interest and discipline can reach a level of quality and artistry that is comparable to the work of those who make the same pursuit the center of their lives.

ABOUT THE CURATOR

Joseph Webb is a photographer based in Orange County, California. Originally from southern Oregon, he relocated to Portland to attend Pacific Northwest College of Art, earning a BFA in General Fine Arts in 2011. Since finishing college, he has worked primarily as a staff photographer and art director at several large fashion and retail brands. While his vocation involves a great deal of work in digital imaging processes, his personal artistic practice consists largely of documentary work and is strictly analog. In 2020, he established a color darkroom printing studio, Myth Editions (Instagram), which collaborates with film photographers to create and publish small runs of hand-printed photographs.

Connect with Joseph Webb via his Website and his personal Instagram and via Myth Editions!

Shadow Gather’s photos unveil nightlife’s raw, electric energy as spaces of defiant authenticity. Her Meow Wolf exhibition elevates marginalized stories, embracing imperfections as vital truths. Each image is a protest against sanitization, celebrating unguarded moments of liberation.