Feature: Jim Steg’s Inspired Journey

Figure 1

Jim Steg (1922-2001) was an inventive artist and dedicated educator blessed with unrelenting curiosity and creative energy. A celebrated printmaker, he used every print-making process imaginable, from painting, serigraphy and woodcut printing to photoresist etching, collagraphy and intaglio printing. He pushed the traditional boundaries of what printmaking meant, including the use of new tools like the commercial office photocopying machine.

Making art and teaching were his passions. A professor at Newcomb College and Tulane University in New Orleans, Steg was a tour-de-force in the classroom. Jan Gilbert, one of his students enthused, “What a trailblazer Jim Steg was! His boundless curiosity, intense sense of immediacy, and utilization of unconventional materials and methods characterized his unique approach to printmaking.”

A natural explorer of printmaking potential, Steg became interested in photography late in his career. Traditional photography was also expanding and changing as scientific investigation impacted the industry. In 1947, Edwin H. Land, scientist, inventor and founder of Polaroid Corporation, introduced his one-step process for producing a finished photograph within one minute. Twenty-five years later, he unveiled to the world the revolutionary SX-70 camera and film system that produced self-developing, self-timing color prints outside the camera in minutes. In Land’s eyes, this totally self-contained photography structure was perfect.

Many artists, witnessing this new type of photographic technology, immediately recognized an opportunity for creative expression. What some thought was an outstanding snapshot of kids at the beach, others viewed as an “unfinished canvas,” begging for a personal touch. Among the first artists to experiment with this film was the Greek-born American artist Lucas Samaras. He had been embellishing his Polacolor self-portraits with designs in ink and paint since the 1960s, so with the launch of the SX-70 camera in 1972, Samaras started to experiment on the developing film by pushing a stylus across its surface, thus propelling its emerging dyes beyond their intended parameters. Straight forward self-portraits were transformed into manipulated, surreal versions of reality within minutes. Perhaps Jim Steg, who often exhibited his artwork in New York City and was aware of its art scene, discovered Samaras’ manipulated SX-70 photographs and was similarly seduced by the film’s inherent potential.

It quickly became clear that artists and photographers were discovering this new artistic tool that could help them investigate and visualize their own ideas – instantly and easily.

How did this unique, photographic magic work? Years of scientific experimentation in laboratories eventually unlocked the secrets of the instant photographic process. Initially, the photographs were sepia, then black-and-white and in 1963 instant color film was invented. This technology was state of the art. When a picture is snapped, the film immediately exits the camera, causing chemicals to spread between the transparent top and black bottom plastic surfaces. Within this sandwich-like space, opacifying dyes immediately create a chemical darkroom that allows the photographic image to develop in the light. Simultaneously, additional chemical activity takes place within the exposed film. The dyes that are exposed begin to migrate upward to the image receiving sheet of the film’s positive layer where one can watch the picture develop. As it takes about four hours for the dyes to harden in place, an astonishing window of opportunity is opened, enticing investigation.

Figure 2

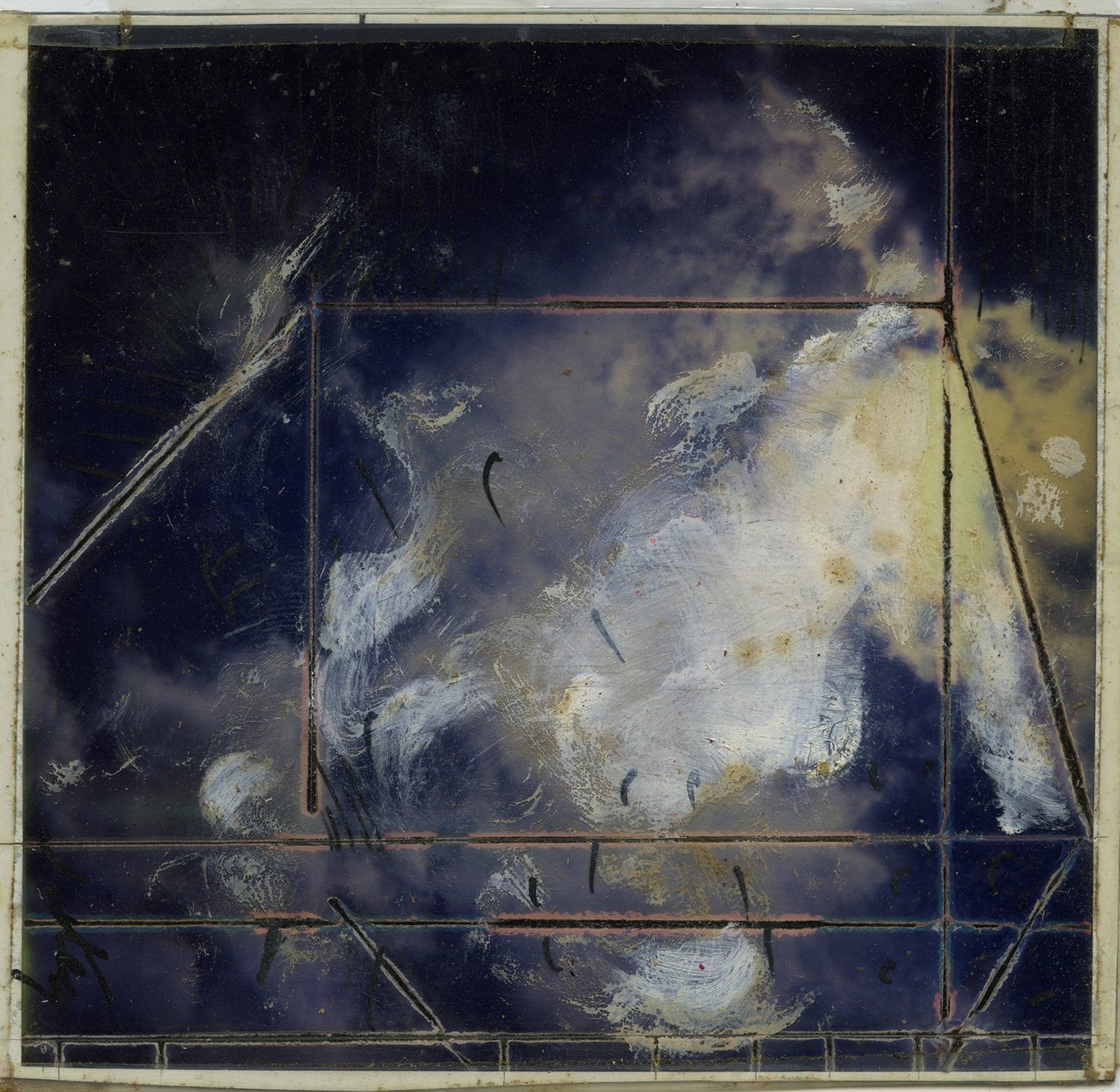

To Jim Steg, this innovation was an invitation to creative intervention. Using almost any stylus-like instrument -- blunt or pointed, kitchen knife or spoon, metal brad or plastic swizzle stick -- one can mix, manipulate or push aside the dye layers. Steg’s two close-up photos of amorphous, soft-edged women illustrate such stylus work as he defines the contours of their faces and outlines their hair in white, magenta and black strokes. (Figure 1) Wanting even more creative control, he cut the Polaroid film, tearing the transparent plastic surface off the film’s black backing. With slashes of blue paint, he defines the models’ eyes and dabs red color on her lips (Figure 2) as the image slowly appears on the positive layer of the film.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

A white layer of titanium dioxide opacifier coats the film’s internal surfaces. It can serve as part of a photographic image or it can be partially or completely scraped off in order to retain only the parts of the photograph that are integral to the artist’s vision. An example of this strategy is Steg’s white-faced woman (Figure 3) with her blue eyes and hair drawn on top of the dried and crazed chemical surface. Once the image he desires is realized, he reunites the front and back plastic film sheets to restore the SX-70s original white plastic frame.

Steg often photographed his subject, manipulated the image as it developed, and then painted over the image on the outside surface of the film. Occasionally, he cut strips of other developed images, collaged them on sections of fully-developed photographs and judiciously swiped and daubed paint where inspiration directed. Perfect examples of this method are Steg’s rendering of a dark, Picassoesque female head and torso (Figure 4) as well as an abstract, expressionistic female nude with raised arms. (Figure 5)

Whether the images that Jim Steg created are relatively straight forward or highly manipulated, they were innovative, unique and exceedingly personal. His artistic journey was one of constant inquiry and exploration. His creative spirit turned on its head Edwin Land’s belief in the absolute perfection of SX-70 film. To our delight, Jim Steg proved that each SX-70 photograph could actually be a starting point that inspires experimentation, that spurs invention and that reveals images previously conjured only within the mind’s eye. Fortunately, we all are the beneficiaries of this world of riches.

Analog Forever Magazine wishes to thank photographic artist and dear friend Jennifer Shaw for facilitating this article, as well as editing and sequencing the gallery of Jim Steg images you see here.

GALLERY

EXHIBITION

Jim Steg: Polaroids opens Dec 10 at UNO St. Claude Gallery in New Orleans, LA, in conjunction with the PhotoNOLA Festival. The exhibition, co-curated by Russell Lord and Jennifer Shaw, will be on view through Jan 8, 2023. Gallery hours are 12pm – 5pm Saturday and Sunday, and by appointment. (Closed Dec 24 + 25)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Barbara Hitchcock, former Cultural Affairs director and Curator, the Polaroid Collections, worked for the Polaroid Corporation.

She acquired fine art photographs for Polaroid, managed its multi-million dollar art collections and its traveling exhibitions. She has been the curator of numerous exhibitions, including Sightseeing: A Space Panorama, a collaboration with NASA; It’s a Dog’s Life: Photographs by William Wegman; Ansel Adams & Edwin Land: Art, Science & Invention; From Lead into Gold: The World of Victor Raphael; and Patrick Nagatani: Themes and Variations. Hitchcock and William Ewing are co-curators of The Polaroid Project: At the Intersection of Art and Technology and the editors of the exhibition’s accompanying book (Thames & Hudson, 2017). During the late 1980s and 1990s, she oversaw Polaroid’s 20x24-studio program, expanding both its artist support and commercial growth.

Hitchcock has served as a juror for non-profit organizations, most notably, the National Endowment for the Arts, Visual Arts Fellowship. She served on the Photography Collection Committee of Harvard University Art Museums for more than a decade. She was president of the Board of Directors of the Photographic Resource Center at Boston University (1995-1998), served on The President's Council of the International Center of Photography, New York, and on the Board of Directors of the Griffin Museum of Photography, Winchester. In 2006, the Griffin Museum presented its first Focus Award to Hitchcock for her critical contributions to the promotion of photography as a fine art. She received a Lifetime Achievement Award for her contribution to photography from the Photographic Resource Center in 2010.

Hitchcock has edited and produced books and exhibition catalogues, among them, Emerging Bodies: Nudes from the Polaroid Collections (Edition Stemmle, 2000); the Selections from the Polaroid Collection series (Verlag Photographie); Lucas Samaras: Polaroid Photographs, 1969-1983; and Sightseeing: A Space Panorama (Knopf). She has authored essays for a number of publications, most recently From Polaroid to Impossible (Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2011); Desire For Magic: Patrick Nagatani 1978-2008 (University of New Mexico Art Museum, 2010); Private Views: Barbara Crane (Aperture, 2009); The Polaroid Book (Taschen, 2005); American Perspectives: Photographs from the Polaroid Collection (Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, 2000). She edited PhotoEducation, a biannual Polaroid newsletter for college-level teachers of photography and has written articles about photography that have been published internationally.

Hitchcock received a BA in English from Skidmore College, a PDM from Simmons Graduate School of Management and Honors in Business Administration and Journalism from Boston College.

Shadow Gather’s photos unveil nightlife’s raw, electric energy as spaces of defiant authenticity. Her Meow Wolf exhibition elevates marginalized stories, embracing imperfections as vital truths. Each image is a protest against sanitization, celebrating unguarded moments of liberation.