Interview: Cary Norton - "Where You Come From is Gone"

Weedon Island, Pinellas County, Florida, 2020

I first became familiar with Cary Norton’s work 12 years ago when I found his Legotron 4x5 camera on the internet. Yes, this was before Instagram, when you followed people’s blogs to see what they were up to. As an analog nerd, I was enthralled with this feat of engineering that shoots film. I have had the pleasure of getting to know Cary over the years but actually met him for the first time last year while on assignment for National Geographic. I can say confidently through the first-hand experience that he is the MacGyver of camera building. There is probably not a camera problem he couldn’t solve with enough time, a few tools, and gaffer’s tape. The neat thing is that with all of his talent and skill with building, he has a tremendous voice with his photography. He navigates both the fine art and editorial worlds seamlessly. He’s soft-spoken but yet passionate about his work, and it shows in his wonderful photographs.

I am excited to share our interview where we focused mostly on his ongoing collaborative project with Jared Ragland called Where You Come From is Gone. This project seeks to “make known a history that has largely been eliminated and make visible the erasure that occurred in the American South between Hernando de Soto’s first exploitation of native peoples in the 16th century and Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act 300 years later.” 1

These landscapes of indigenous sites are made in Cary’s backyard of Alabama and also in Florida. The images show a certain passage of time and bring to light the history of Native American cultures that are no longer here, but the memory and remnants of this rich but challenging history remain. The beauty of these wet plate photographs takes me back to history and culture that some have neglected, whether deliberately or inadvertently. The images hold a beauty to them of a forgotten past that needs to be remembered and cherished.

Catherine Wilkins, Ph.D., “Where You Come From Is Gone” project statement

INTERVIEW

Rashod Taylor: Tell me a little about yourself and your earliest memory with photography?

Cary Norton: So I grew up in Tennessee, but I've been in Birmingham, Alabama for I don't know, 20 something years. So, it's definitely home. I've always been interested in anything visual, anything mechanical, that kind of thing. From a young age, I think I was either five or six for Christmas and had an all Voltron Christmas. I got a Voltron camera that shot 110 film, and you could expand it out to be the Voltron action figure. But it was also a terrible camera, but functional. And that was sort of my first taste of it.

RT: You shoot both commercially and fine art projects. How do you balance shooting for yourself vs shooting for others?

CN: It's really funny, for a long time the balance was there naturally. Then I got more and more and more work. And there were a couple of years where all I did was work; I got a spreadsheet. And then I have all of my personal work in its own area on my computer. For a couple of years, it's like there's almost nothing there. I was miserable during those two years. I realized that it's because I wasn't shooting nearly enough personal work. This last year during the pandemic and everything has been really informative for me, too, that they kind of feed each other. Now I find when I'm doing commercial work and editorial work and that kind of stuff. I like doing that work, but I get to a point where it's like, Okay, I need relief from that. And that's what sort of throws me back into my personal work, which is almost entirely film. I slip in film, into editorial work whenever I can. Most of the time, there's no budget for it, but I'm more interested in it. When it fits I try to slip it in there, budget or no.

Bessemer Mounds, Jefferson County, Alabama, 2017Ten Islands, St. Claire County, Alabama, 2017

RT: I want to talk about the project with Jared Ragland, Where You Come From Is Gone. The plates you and Jared have made are spectacular and very meaningful. Tell us a little more about how this project started?

CN: Jared and I are part of group of photo nerds here in Birmingham, Alabama, and he and I both had expressed appreciation for tintypes and the desire to learn how to do them. One night we were both just like, “I'll do it if you do it.” So, we set out how to learn and figure out how to learn the process. My buddy Scott Stallings gave us a one-day workshop back in 2015 and it took us a while to get all our stuff together. Then once we got our portraiture down, the most logical step for us was to take it outside. And if you're going to go through the effort of going outside with it, we really wanted to have a project to really dig into and go deep with. So, we started digging into the history of Alabama – initially, of the iron industry in Birmingham, then we began thinking about Indigenous history across the state.

Here in Alabama, place names like Tallassee, Coosa, Ohatchee, and Cahaba are common. Of course we recognize them as Indigenous names, but before we started this project we knew little of their specific history or importance. In some places historic markers might be present, but many times the stories they tell recount a white, western-driven narrative that privileges colonialist perspectives while overwriting or altogether erasing, Indigenous histories. So the project has provided an opportunity for us to relearn the history of our home and recognize the great injustices that occurred here.

We titled the project, “Where You Come From Is Gone” – a phrase taken from Flannery O’Connor’s Wiseblood. On the surface the title feels like we're talking about the disappearance of Indigenous places, but instead its really about how the histories we grew up with – again, those privileged, colonial narratives – that aren’t really true and should be challenged.

RT: I look at these images, there's this eerie feeling I get which is enhanced once you understand the history with some of these places. They can be emotionally charged. What leads you to some of the locations?

CN: Jared and I do a lot of reading, we research period texts and maps, and we do a lot of driving. At this point I think we’ve driven more than 3,000 miles across 30 counties in Alabama and Florida to locate and visit a variety of places – from former sites of Creek mothertowns, sites of battles and massacres, and sacred burial lands. The pictures are intentionally melancholic and they’re deliberately designed to document absence and record what has been lost in a way that reflects the sacredness of these spaces.

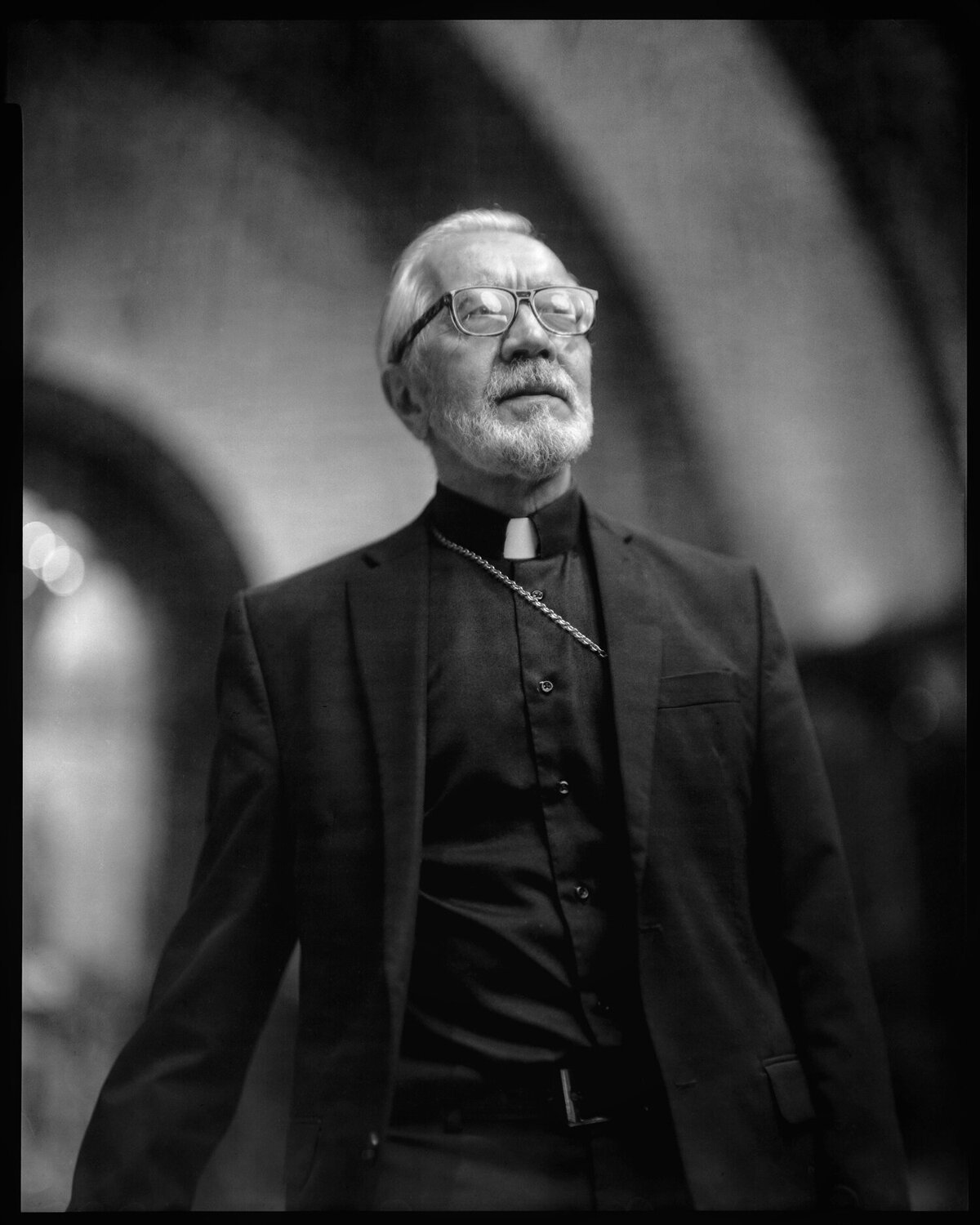

RT: The image titled Jungle Prada Site, Pinellas County, Florida, 2020. It's a really heavy photo. Tell me about this site as it reminds me of a burial ground with skulls and bones scattered everywhere.

CN: Yeah, Jungle Prada is a Tocobaga mound that’s more than a thousand years old. It’s a midden mound made from shells, and in the picture the shells do feel like bones – which was intentional because we knew the site would provide an opportunity to illustrate the mass genocide that happened across the Americas following the Spanish conquistadors’ exploration. It was at or near Jungle Prada in 1528 that Spanish conquistador Pánfilo de Narváez landed and performed the first Catholic Mass in Florida, declaring divine right to the land. Scholars estimate that between 1492-1832, more than 1.86 million Spaniards settled in the Americas. Conversely, the indigenous population plummeted by an estimated 80% in the first century and a half of colonial exploration, primarily due to the spread of Afro-Eurasian disease.

RT: How has this series impacted you personally?

CN: This has been fascinating for me, to not only learn something about my adopted state, but to learn, possibly a more clear, more honest version of that history. And we feel that it's incumbent on us to responsibly and thoughtfully recognize that where we live has been injured through past exploitation. For us, making this work is a kind of act of responsible citizenship and hopefully improves our understanding of ourselves in relation to our home and to others.

Ten Islands, St. Claire County, Alabama, 2017

RT: Tell me about the significance of using wet plate for the series.

CN: I think about the seriousness of the work and the connections that we want to make to the stories that we're discovering – I've always enjoyed shooting large format and there's something about shooting wetplate that's at even another level. It’s an intensive, laborious process.

Before we make any pictures we spend a lot of time in the landscape – sometimes several hours – exploring and becoming familiar with the environment, considering how and what we see might match the aesthetic and conceptual goals of the project, then finally preparing and making a plate.

Catherine Wilkins, who has written about the project on several occasions, points out that it is just this type of spatial involvement and prolonged, close physical engagement with a location that helps cultivate local and historical literacy – which is exactly what we hope to accomplish with the work. So it’s the wetplate process – with all its labor intensiveness and possible flaws - that helps us get there.

RT: You shoot mostly digital for commercial and editorial work, but you have a love for film and analog processes. Why is that? What keeps you coming back to analog?

CN: It's just, it's physically there. It's different and engages differently. Like shooting a roll is different than shooting a GFX that you can flip your screen up with. When you look right on a digital it goes right, instead of going backward. Looking at the back of a 4x5 or an 8x10 or anything bigger, it's upside down and backward, and it's a different engagement type. Like the composition you're making, you have to completely think about it. You put me in the room with a camera made out of a cardboard box, or an 8x10, or like a black room with a pinhole to the outside, and I got to make a portrait with a camera obscura. I'm excited by that. That type of photography is so much more exciting and interesting to me. Even though I make my money making work digitally most of the time, that's why I keep coming back to film, because it's wild and it's unpredictable. You can kind of do it with anything; like Legos, cardboard, wood, plastic, a whole building – like Brendan Barry (@brendanbarryphoto), and make a skyscraper into a giant camera obscura.

Tierra Verde, Pinellas County, Florida, 2020

RT: Who are some photographers who have either influenced your work or have made an impact in your life?

CN: Shoutout John Dolan (@johndolanphotog) and Holger Thoss (@holgerthoss) and Philppe Cheng (@philippecheng). Those dudes are amazing. I could talk about them forever. They each have their own ways that they impacted the way I think about my own work and the way I see things. Also, sub-shoutout to Anne Watkins (@annewatkinswatercolor). That's a whole other story. She’s a gestural watercolor painter in New York. Amazing, beautiful human beings, all four of them.

RT: What's next for you? Do you have any other projects in the works? Or ongoing things that you're working on?

CN: Yes, the biggest thing right now is still wet plate-related. I had an arts grant from the state of Alabama last year. Most of the world was on fire last year, so things didn't go quite as they were intended to. I did get the grant to continue this wet plate work and continue it in a way that was project-specific, as well as most of my life is portraiture. So, that was part of the grant as well. And that grant was to build a 16x20 field camera. In order to make it shoot, horizontally or vertically, which is to say landscape and portrait, it's really a 20x20 camera that I started building in 2020. I've still got a little bit of stuff to do to it, and it will be a field camera on paper, but it's enormous. We'll see how she shoots a plate that size and the field goes. But that's the thing I've been working on, off and on here and there. I mean, I have all sorts of other stuff going on in life. So I haven't finished it just yet.

GALLERY

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Cary Norton is a fine art and editorial photographer, camera builder, and beekeeper. In 2009 he received worldwide recognition for building a 4x5” field camera from LEGO blocks, and he is currently at work constructing a custom 16x20” large format camera from locally sourced lumber and iron. Cary has worked on long-term assignments in London and Baghdad and worked with NGOs in India, Kenya, and Uganda. In addition to client work for Ford Motor Co., Regions Bank, Verizon, and Whole Foods Market, his photographs are in the collection of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art and have been published by Smithsonian Magazine, Southern Living, and The New York Times. Cary is an alumnus of Samford University, and he resides near his apiary in the Avondale neighborhood of Birmingham, Alabama with his wife Stephanie and their two Dachshund rescues, Fin and Munch.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rashod Taylor is a fine art and portrait photographer whose work addresses themes of family, culture, legacy, and the black experience. He attended Murray State University and received a Bachelor's degree in Art with a specialization in Fine Art Photography. Since then, Rashod has exhibited and published his work across the United States and internationally. His work is currently on exhibit in the group show, Reflecting Voices at the Colorado Photographic Arts Center in Denver, CO. He is a 2020 Critical Mass Top 50 Finalist, winner of Lens Culture’s Critics Choice award, and a 2021 Feature Shoot Emerging Photography Awards winner. Rashod’s clients include National Geographic, The Atlantic, Buzzfeed News, and Essence Magazine. He is currently working on a series called Little Black Boy, where he documents his son’s life while examining the Black American experience and fatherhood. He lives in Bloomington, IL, with his wife and son.

Connect with Rashod Taylor on his Website and on Instagram!

Camille Valbusa’s self-portraits are critical identity studies that research artistic practices of healing from trauma. Read our latest interview where she dives into the motivations of her photography, talks about a current book project, and how shooting film plays into her art-making practice.