Interview: Eric Kunsman - Historical Narrative

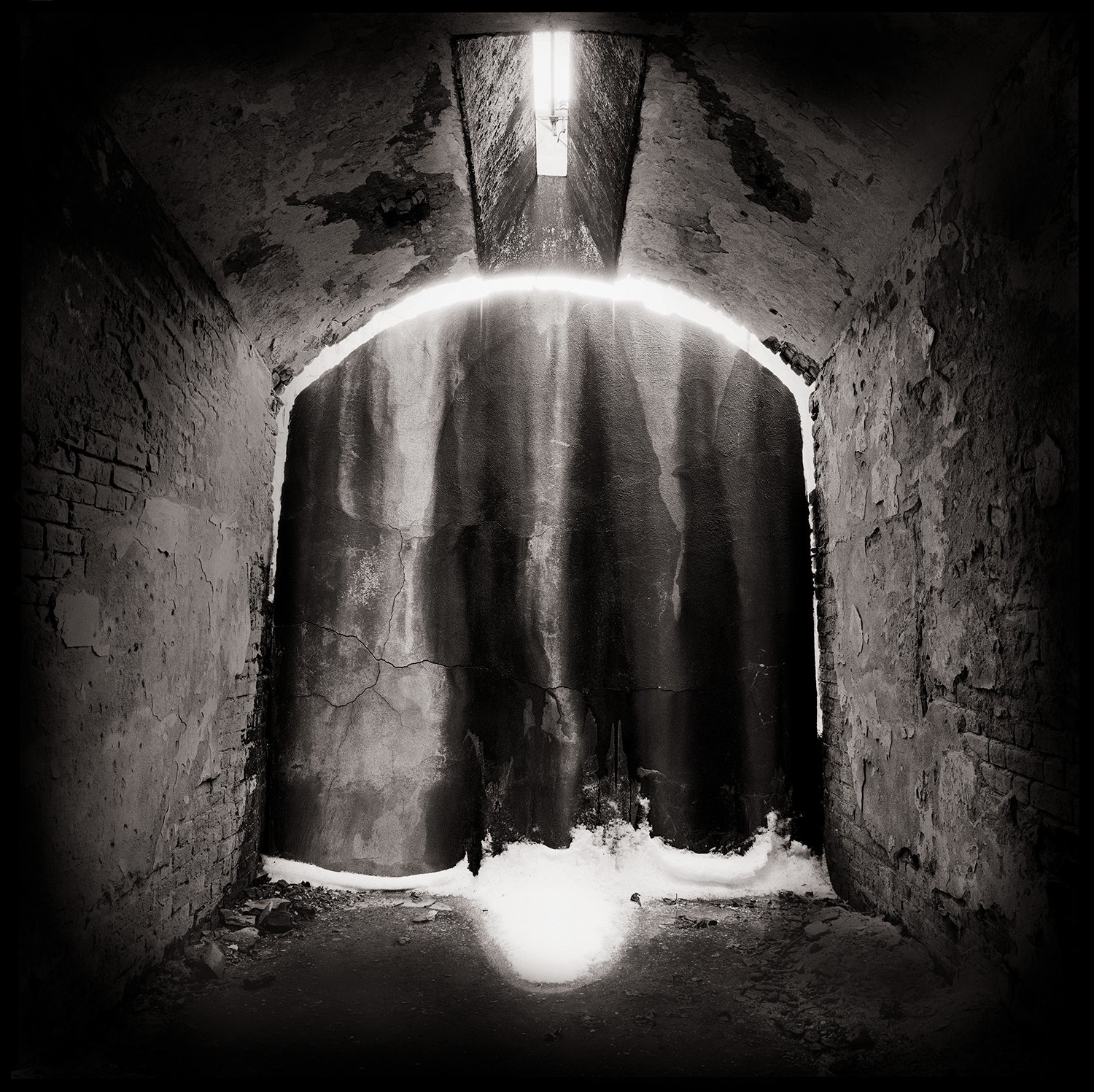

“Entrance to the Infirmary” from the series Thou Art…, Will Give…

Photographer, entrepreneur, and educator, Eric Kunsman, has made it a goal to carve out a wonderful life and career in his upstate New York home of Rochester. By all accounts it looks as though he is succeeding quite gracefully. Originally born and raised in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, Eric was heavily influenced as a witness to the eventual death of the steel industry in the Rust Belt of America. His educational direction has led him to hold his MFA in Book Arts/Printmaking from The University of the Arts in Philadelphia, as well as an MS in Electronic Publishing/Graphic Arts Media, BS in Biomedical Photography, and BFA in Fine Art photography, all from the Rochester Institute of Technology. Later, taking these influences, making Rochester his permanent home, Eric proceeded to engage with photography as an artist documenting the societal changes around him, while also starting a digital printmaking business, Booksmart Studio, and starting a family.

Kunsman's images rely on a classic and timeless feeling created with everything from medium format film for his documentary work, to the use of instant film for bringing creativity and nuance to images in his premiere collection, Thou Art…, Will Give… Indeed, it is this series created while investigating the historical, and former, Eastern State Penitentiary, in Pennsylvania, that first caught our attention. Upon further examination of his works, however, it was clear that Eric’s use of film and analog cameras brought life to two other notable and ongoing collections, PRIVATE | Now Back Go : Go Back | PRIVATE, and Felicific Calculus. Both of these bodies of work examine the current state of being in the Rochester area brought on by changes in society and technology from different perspectives. Lacking human representation in the photos themselves, they are very much portraits of place, and one informed by the denizens who have previously passed through. In this discovery, we’ve decided to include a small selection of these works to wet your appetite for more, from the dedicated efforts of a photographer looking to the future while learning from the past.

It is quite clear from understanding the trajectory Eric has taken in originally learning and practicing photography from an analog perspective, and then applying that practice and knowledge into the realm of digital negative and print making, for both himself and those photographers looking to collaborate. Without the film sensibilities earned early on, the digital world would clearly have no direction, and it is with Eric’s stewardship that he and others can continue to make work from a symbiotic hybrid process of the two. However, do not sit idly by and let us simply show you Eric’s works here. Take some time to visit his website, or an exhibition of his prints, and discover more about this prolific photographer and the efforts he has put into his beautiful and thought-provoking photographs.

Lastly, it only makes sense to include some Q&A from a talent like Eric. His workshops and classes at RIT, now as an educator, are on par with the high level of commitment he has achieved with his photography and print making. It is with great honor that Eric has taken the time to collaborate with us and answer some questions about his images, process, and aesthetic. We hope that you learn and enjoy the experiences that Eric Kunsman has worked so hard for, and illustrated for us in this interview. Before you begin reading make sure to connect with Eric on his Website and Instagram!

Interview

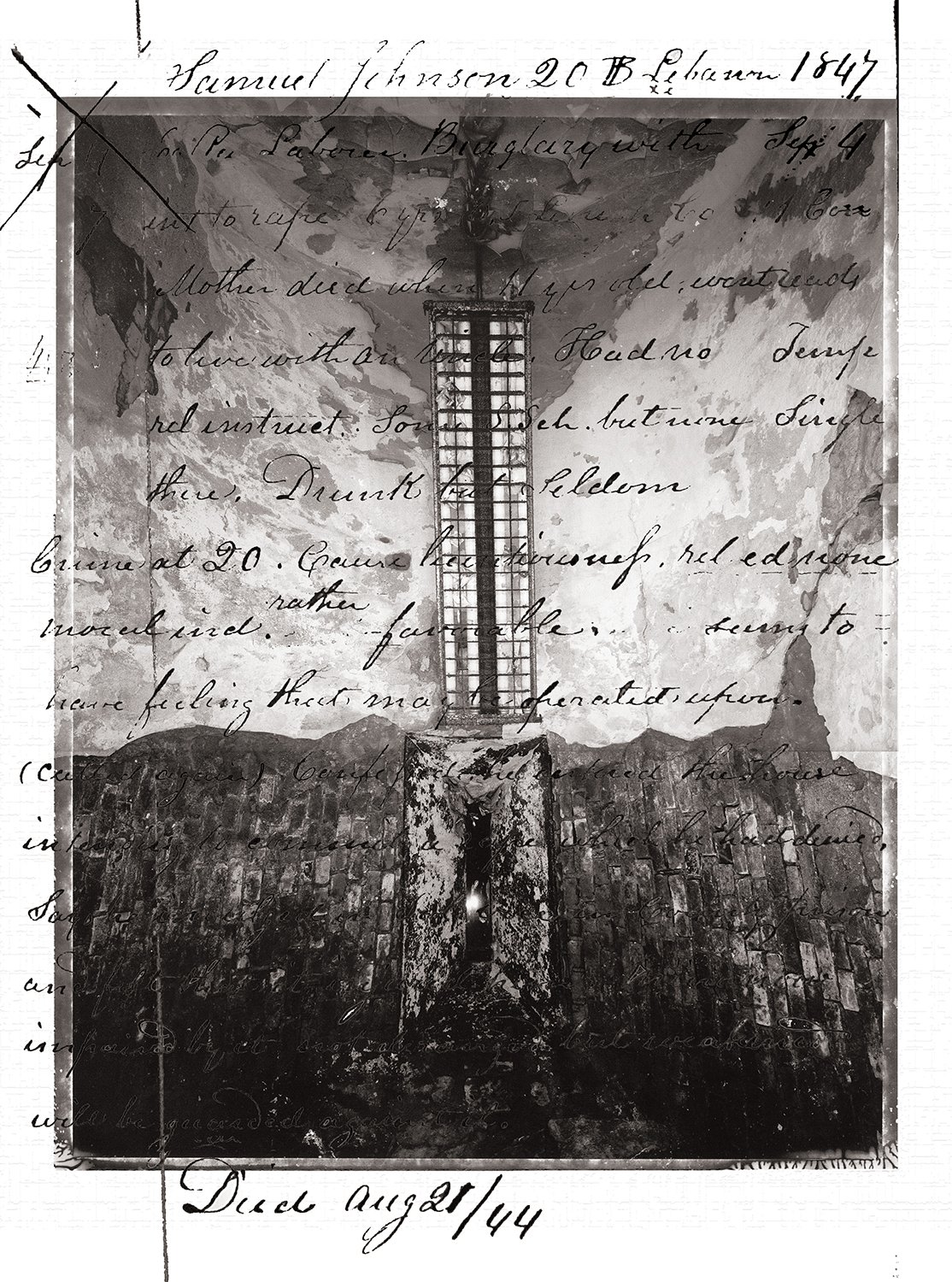

“Ashes” from the series Thou Art…, Will Give…

Michael Kirchoff: Thanks for joining us here, Eric. First off, how about some background on what interested you enough about photography to make it your career? Was there any influence from family or any individual who inspired you to explore the medium?

Eric Kunsman: In all honesty, once I picked up a camera in 11th grade I never put it down. From the time I was a very young age, maybe 1st or 2nd grade, I knew I wanted to be an artist. In fact, during the school year when it was not wrestling season, I airbrushed T-shirts at a local mall, and later at an amusement park. The irony is that airbrushing helped pay my way through school at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT), as I used the funds to pay for my supplies.

While in high school, the Bethlehem Steel was slowly closing and many photojournalists descended on my hometown. It was one day in my high school photography class that my teacher, Mr. King, showed us the work of Walker Evans and the images he took of the Lehigh Valley, including Bethlehem. It was at that point I realized how photography can be used to shape and document history. I was hooked!

As for family influences, my father had a 35mm camera but I never remember seeing him pick it up. My father was curious that I decided to take a photography class in high school since I had always been drawing or painting, since as early as he could remember. My father was a roofer and never had time or energy to explore his desire to photograph, so to this day I do not know if that was his interest. My parents’ focus was working to provide for their children and to make sure my brothers and I got to every wrestling tournament. Another family influence was my Aunt Karen who was a Rhode Island School of Design graduate, and was always giving us drawings or etchings as Christmas gifts when I was a young child. This had an influence on me and helped me to realize that adults can also make art, and that it wasn’t only for kids.

MK: Since we are doing this for an analog photography publication, I wonder if your start in photography included things like processing and printing your own images in a darkroom, or was it something that came to you later in life as a different way to express your ideas?

EK: My start in photography began completely in the darkroom and I learned from some incredible mentors. Luckily, I have had photography as my lifeline since high school, and was able to study at the Rochester Institute of Technology. I spent many nights working and sleeping in the darkrooms. I had the luxury of studying with Willie Osterman, who was an assistant to Ansel Adams, so I learned the Zone System thoroughly through his class. Owen Butler from RIT was another proponent in the way that I approach my photography. However, no single mentor had a bigger impact on me than Lou Draper. Through Lou’s mentorship I learned more about my visualization process, approach to being an educator, what it means to be a photographer, how society can influence us, and how we can shape some part of society for the greater good. Lou Draper was a master in the darkroom, as he was one of W. Eugene Smith’s print assistants, and I watched him work his hands in the chemistry like they were magic.

From 1993-1999, I printed everything in the darkroom and have never stopped shooting film. In 1999, is when I started to print exclusively in the digital darkroom with Iris printers, before Epson had sponsored my Masters of Science thesis in 2000, which was on high density black & white digital printing, utilizing inkjet printers. Again, I have never stopped shooting film for my projects, but I do shoot digital at times when I do not need my genuine creative/visualization process. However, the ultimate control I have within the digital darkroom is the last part of my visualization process, which provides the control I desire to create the emotional attachment I try to provide the viewer. Currently, when I work in the darkroom, I utilize digital negatives and non-silver processes. Non-silver prints allow me to work with my hands just as the books I produce with traditional bookbinding techniques.

“Jefse DE Quantrill” from the series Thou Art…, Will Give…

“Solitude” from the series Thou Art…, Will Give…

MK: What is it that inspires you to decide upon a particular project?

EK: Honestly, that is project dependent, as each project has been motivated by certain life influences or environmental/societal circumstances. Growing up in Bethlehem, PA I was influenced by history and the role that Bethlehem held on shaping the United States. As I watched the steel industry die, it captivated my interest to dig deeper into photography and the influences it has on society and history. Since that early influence, I noticed that there is either a sociological or historical component that triggers my projects.

I truly believe that my projects have found me due to my life influences and that I never plan on what is next. It puts a smile on my face when I think about the influences for each of my projects. I can truly say that each fork in the road has led me to be where I am today and I truly appreciate each moment that lead up to where I am. The bad influences are what have helped me to create certain bodies of work along with the good life experiences.

MK: Do you study what others are doing, and do you find their influence in your own image making?

EK: I often look at images, whether on social media, the library at RIT, or my own photography book library. I don’t really study the work to look for inspiration or influence for my own work. Instead, I like to know what other people are working on to see the contemporary landscape. My work is more influenced by relationships I have created with fellow photographers and discussions we hold along with my students at RIT. My work is also often influenced by simple conversations I have with the individuals in the communities that I am documenting. One of my favorite parts of the Felicific Calculus series is the dialog that starts with random strangers on the street (from ALL walks of life), once they learn that I am documenting the payphones of Rochester, NY. I have learned so much from these individuals, and our conversations serve as more of an influence than any photographs I looked at previously. The payphone project and the surrounding conversations truly humbled me unlike any other project to date. In return, I have an attachment with these inanimate objects I am photographing because of the dialog surrounding the project. The influence of this project has started to take over my entire family as my daughter, Viviana (4), son Bryce (9), and my wife Sandra, have all become involved with this project in one way or another. At this time, my daughter Viviana is my biggest critic and supporter for this project.

“Thou Art Will Give” from the series Thou Art…, Will Give…

MK: I wanted to go over a couple of bodies of work from you that have employed the use of film to make the work, and the first is Thou Art…, Will Give…, which is a quite ambitious project in its execution. To start, can you tell us a brief description of what led you to create this collection?

EK: I first visited the penitentiary with my students from Mercer County Community College (MCCC) on days the museum was closed to the general public. I would literally have to confine the students to certain areas of the penitentiary for the day, because otherwise they would become overwhelmed with the architectural ruin aspect. The students would be disappointed when all they created were tourist snapshots, and nothing they thought they were capturing of the space. During these photographic opportunities I never picked up a camera, as I had no attraction to the penitentiary, as it was just another building with peeling paint.

A few months later, on a visit to the American Philosophical Society, which is part of Independence Hall, I was visiting the conservation lab. My professor Heide Kyle was the head conservator and we were there for a class field trip. While I was coordinating the photography program at MCCC I was also working on my MFA at The University of the Arts in Book Arts & Printmaking. Heidi was our bookbinding professor and had prepared a slew of books for us to look at. As soon as I walked in the door and looked down, I read a cover that stated Warden’s Logbook Eastern State Penitentiary. As I idly opened the logbook, I became enamored in the voice the Warden’s passages provided. I did not look at any of the other books that Heidi had provided to the class and do not remember listening to a word she said during that visit.

Luckily for me, the books were in such bad shape they could not be viewed by the public. I made an agreement with Heidi to come in and photograph every page of all nine logbooks so that future researchers could have access to the books digitally. I was then also able to use the logbooks for my research. If I had never discovered the Warden’s logbooks, I would have never started the work, as there would have been no narrative for me.

The narrative was provided by reading 4-6 pages of the logbooks and then reflecting on the Warden’s writing each day. I visited the Penitentiary over the course of three years, 362 days to be exact. The Eastern State Penitentiary provided me with full access for those three years, thanks to an agreement with University of the Arts that a book about the work would be published. The book was to be available for sale at the museum’s gift shop. Unfortunately, to date the book has not been published, which is the last piece required to complete this project.

MK: With Thou Art…, Will Give…, and the years of returning to the abandoned Eastern State Penitentiary, you’d mentioned in your artists statement that you would often reflect upon the words of the warden’s writings before beginning to make photographs. Do you feel this was somewhat of a requirement of yourself to allow these words to direct your actions? Why?

EK: Absolutely, because the words are what provided the voice and narrative I was trying to capture during each visit. The words truly prevented me from falling into the trap of just recording the penitentiary as just another ruin. On each day, I would randomly pick a space to confine myself into so that I would not be overwhelmed with the physical characteristics that often happened to my students. I wasn’t trying to feel as if I was in solitaire, but just used this as a tool to make sure I was looking at the space with a concentrated focus for the day. I confined myself into many spaces multiple times and it was amazing how the warden’s words really did change my vision, as well as being focused on one area many times.

When I first told David Graham, a photography professor from the University of the Arts that I was photographing at ESP for my thesis work. He stated “no original photographs can be taken in that place because there are tripod holes everywhere.” David would know, as the University of the Arts photography program would also rent out the penitentiary for their students to photograph. I accepted that as a challenge and knew that I had the Warden’s voice on my side. I will never forget the moment that David walked up to me at my first thesis exhibition and slapped me on the shoulder and said, “Way to make your own tripod holes”, and continued walking away. Everyone else just looked at me as I smiled, knowing exactly what he meant in his compliment.

‘Cellblock 5” from the series Thou Art…, Will Give…

“Most Deeply Hardened” from the series Thou Art…, Will Give…

MK: In looking through the entire collection of Thou Art…, Will Give…, it seems as though you employed the use of a couple of different formats, tones, and film types. Why is this, and was this necessary to illustrate your vision for how the work would look as a whole?

EK: To be honest, the different formats were dependent on my working speed and the ability to capture what I was feeling each day. Towards the end of the project, I was working primarily with the medium format camera because I was leaving the Philadelphia area and moving back to Rochester, NY. I felt a sense of pressure to capture everything I was feeling about the space and had only a few months left to do so.

I first started the project using Polaroid Type 55 because I felt it was required for the architecture, and I knew the only film I had time to develop was the Type 55, due to my intense schedule of teaching and taking classes. Later in the project, I realized that with my use of wide-angle lenses I did not have to use 4x5 and that my sense of the place was captured better in the confines of the square format.

As far as the different tonal values, that again helped me to illustrate the narrative of my reflections on the words I read each day before photographing. The use of painting with light really allowed me to express the narrative through my use of controlled lighting. Along with painting with light, I also employed tonal manipulation techniques in the digital darkroom when I did not capture the environment of the image as intended when painting with light.

“The Drapery” from the series Thou Art…, Will Give…

MK: Do you feel as though there is one signature image from this collection that gives voice to the work as a whole?

EK: The one image that most viewers tend to resonate with is “The Drapery.” Individuals read the image differently, but the common reoccurrence is the underlying tone of despair and hopelessness. I think it is the mysteriousness and darkness of the image that provides the viewers with the sense of what the prisoners were feeling. This single image is not about the architecture or the words that I overlay within the images. Instead, it is raw emotion and everyone brings their own history and personality into the piece.

Otherwise, I feel the collection of Warden’s logbooks and my images with text and imagery provide the tone to the exhibition. I have had to argue with a few curators to keep the logbooks in the exhibition due to their importance and foundation to the work. The reason is those pieces are not as much about my vision, but rather the voice of the work.

MK: Any exceptionally interesting stories from the making of Thou Art…? You were after all working within a location thought to be one of the most haunted places in the world. Any personal thoughts on the haunted aspect and how it might relate to the work?

EK: I was at the penitentiary a few nights when ghost hunters visited the space. My only stories of “ghost” are only humorous. The first was one evening as the series Ghost Hunters was exploring, and placed infrared cameras everywhere. We discussed which cellblocks they planned to setup their cameras. My assistant and I were outside painting with light, as most of my images are with large three million candle watt lights. My assistant and I had just finished one image and packed up the gear, and were walking away, when the crew came running around a corner asking if we were using strobes as they ran by. We yelled back no and they quickly replied, “They had hit the mother load.” At that point I looked at my assistant and we both realized simultaneously that they thought the flashlight movement was strobes or movements of light. The crew later found us and tried scolding us for messing with their serious work. We informed them they weren’t supposed to be setup in that area, and that we were working with flashlights, and that is why I replied no to their question.

The second experience was one winter day when I was the only person in the penitentiary. I decided to walk through the “Terror Behind the Walls” attraction at Eastern State, which is their haunted prison experience for Halloween. I'd never walked through this area before and as I did a skeleton and other objects lunged at me, as the crew had forgotten to turn off the motion sensors for that area. As I was leaving for the day I walked over to the warm office to inform them they were wasting power, as some of the attractions were still active. They all started laughing and asked why my camera was not damaged, as they thought I would have dropped it.

Unfortunately, that is my extent of ghost stories. I really tried to be open to the experience during my night sessions, and a few days when I was the only person in the penitentiary. I would sit in solitaire in the dark for a few hours to truly open myself up to the opportunity, but just never had much luck.

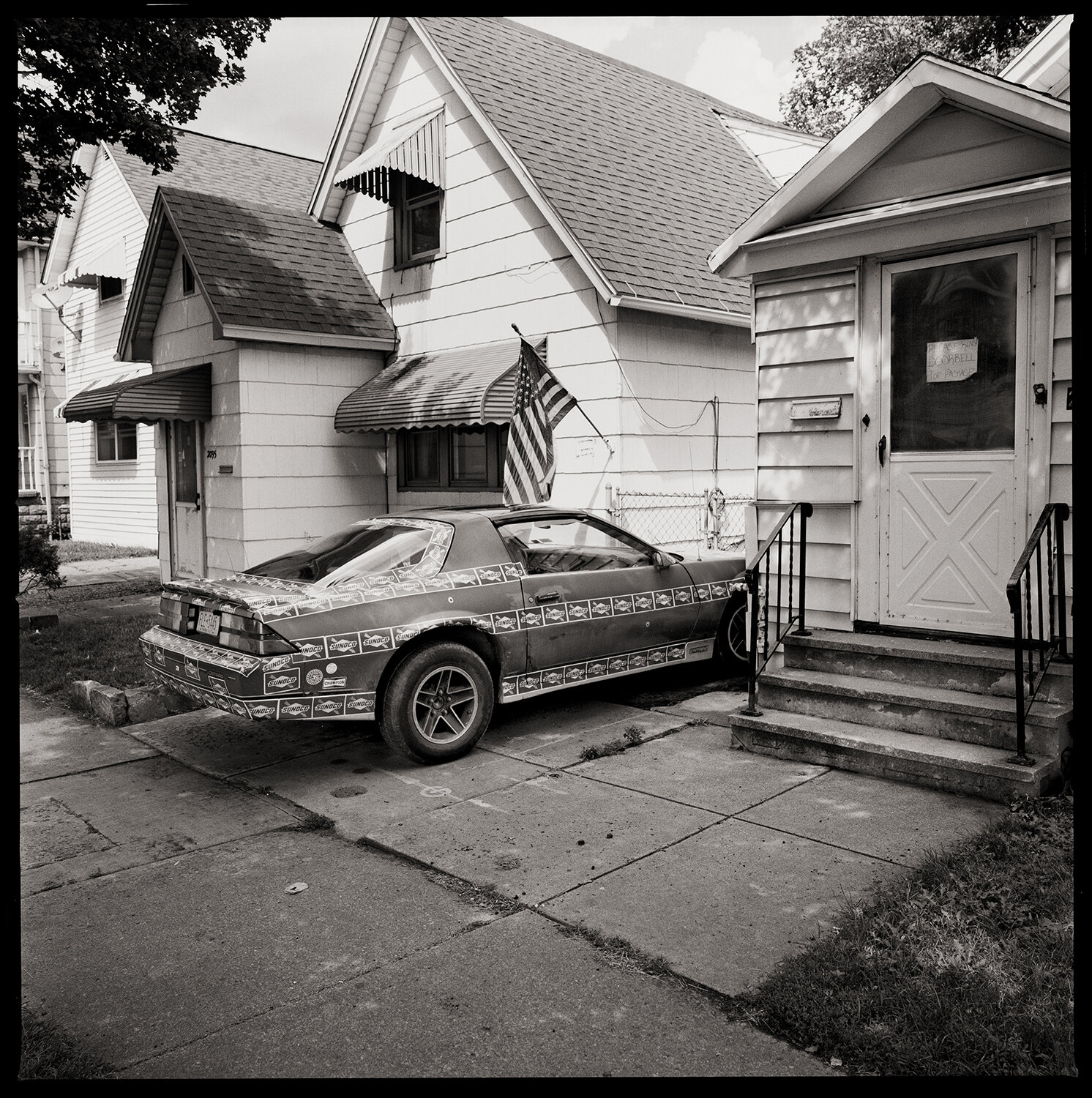

An image from Eric Kunsman’s series Private

MK: For the series, PRIVATE | Now Back Go : Go Back | PRIVATE, you’ve made the brilliant move to use analog means to illustrate your ideas of what technology and progress can do to a society. Was this your intention from the start of the project, or was it something that came along during its creation? For example, the irony of seeing an image of the abandoned Rochester Kodak plant in this context is clearly not lost.

EK: Personally, I have never stopped shooting film. Yes, there were seven years where my business took over and I did not create a single photograph. However, I love analog because when I capture the image it slows me down, and I always ask my students what that means. They state it means I don’t just keep clicking. My definition of it slowing me down is that I take my time observing when I capture an image and do not photograph as much of the scene, and put more of my emotion into the capturing process. More importantly, the lack of seeing the image on the back of the camera allows me to then reflect back on the scene or image I think I created before I have my film developed. Once my film is developed, I can then see if my interpretation comes through and if not, then I may tweak the digital file which allows me to put more of my emotional connection back into the images. It is for this reason I never stopped shooting film. I shoot digital at times, but I have a different frame of mind when I am capturing images with my digital resources and fall into traps. I am also shooting all of the payphones on digital as a back-up to my film, just in case of the event of a processing mistake.

Yes, the irony of the Kodak plant was filled with heartfelt emotion as I was capturing the piece. Sometimes, I am smiling and laughing as I discover some of the scenes I am photographing, and others I am overcome with a sense of sadness as to where our society is heading towards, in regards to our future. The one constant I have in my long-term projects is film, which allows me to reflect on why I create the photographs.

MK: As this is an ongoing project, is there a long term goal for PRIVATE | Now Back Go : Go Back | PRIVATE?

EK: I do not have a goal for this project, and in fact have not previously tried to exhibit it as a body of work. I have only submitted certain images to juried exhibitions and have had some success with those pieces. It wasn’t until recently that I started thinking that I should start to exhibit the work I have in progress at this time. It always just felt like I am in the beginning stage for this body of work. A few weeks ago, I was asked by Float magazine to submit the work for a feature on their website, and I was taken back by that request. I am starting to think that this body of work will go on throughout my life. The series will contain chapters that will also emulate the stages of my life and experiences. This is the first time I believe a body of work will not have an ending, but rather offer a long-term story that will help me to document history and my life experience. I started this body of work in 2012 and is currently the longest running body of work in progress. I’m truly enjoying the idea of no end goal and seeing where it takes me.

An image from Eric Kunsman’s series Private

An image from Eric Kunsman’s series Private

MK: I’ve noticed that with both series Thou Art…, Will Give… and PRIVATE | Now Back Go : Go Back | PRIVATE, the titles have literally come from words within specific images from each. Were these images the inspiration that set you off in the making of these works, or where they simply something that spoke to you when it came to naming each collection?

EK: Those images were simply just something that spoke to me as I was photographing, and knew instantly that they would become the title to the respective body of work. In fact, the PRIVATE | Now Back Go : Go Back | PRIVATE series was originally titled the Upstate Economy and I had to change it because the new title is everything I felt at the time, and continue to feel as I work on this series today.

My image Thou Art… Will Give… was towards the end of the project and I had just read six pages that really discussed the idea of how those prisoners either died in prison or lost their minds. I had been in the Chaplain’s Office many times prior to this visit, but that day as I turned to walk out, I noticed only those four words of a longer prayer passage. It was at that moment that I realized the full meaning behind the project I had been working on for so long with four simple words.

An image from Eric Kunsman’s series Felicific

MK: I love how you grasp your local environment with the series, Felicific Calculus. How did this title come about, and how does this work fit into the framework you’ve built with some of your other analog collections? Is it too required to be a film-based project?

EK: Ironically, this series started when I purchased a building for my company in an area of Rochester that many people deem scary, by Rochester’s soccer & baseball stadium. My old studio that I occupied for ten years was in the Neighborhood of the Arts In Rochester, which includes our Art Museum and the Eastman Museum (formerly the George Eastman House), and is populated with cultural landmarks. I was being told by other RIT faculty and a few friends that the area I moved the studio to is a war zone, and they no longer felt safe going to my new studio.

An image from Eric Kunsman’s series Felicific

However, my experience was completely opposite, as when I backed up my first truck I had three neighborhood kids that were 7 years old come and help me unload the truck. At first they were just moving stuff, and then they asked if they were going to get paid. I explained I didn’t have any cash and they politely asked, “What do you have?” I looked in the cupboards and found coffee mugs the previous owner left and showed them the mugs. They asked if they could have mugs as payment and I said “Of course, but you need to move all of the rolls of paper to the back of the building.” They completed this task and walked off as if I had just paid them each $100. Meanwhile, in my old studio I had just gone through 3 break-ins in a period of 9 months where the crew that hit me took about $85,000 in equipment.

Therefore, I was very torn with individuals’ gut reaction to the neighborhood I just moved into, and their labeling of the people there. As I became introduced to the neighborhood, I started to understand more about the neighbors that live around my studio and have found the labeling of this area to be completely off-base.

At that time in 2017, I started looking around for any social markers or reason that my friends from the suburbs felt so strongly about the “Big Bad Area” that my studio was now located. I started noticing payphones everywhere in this area, including on street corners of neighborhoods. When I asked my colleagues and friends what they thought of payphones they would state, “Only criminals use them”, or “They are only used by people looking for drugs or selling drugs.”

It was at that point I realized that payphones are one of the social markers, but not the only one, that helps form the definition of these areas. I quickly came to realize that these payphones are still a lifeline to many individuals that reside in some of these areas. I started the project and still have a ways to go in recording all 1,455 payphones that are still left in Monroe County. I plan on displaying the photographs of the payphones along with maps that show the relationship of their location to the census information for race, economics, economic growth or retraction, population, and crime maps.

This title, like many other projects before, took a long time again to develop. I was struggling to think about how Frontier Communications has made the decision to lose money on these payphones while still being in trouble financially themselves and how the payphones serve as a social marker at the same time. It is not often that a corporation thinks about the community before profits. I only discovered this as I was working on the project. The definition of a Felicific Calculus, as according to Webster Dictionary is: a method of determining the rightness of an action by balancing the probable pleasures and pains that it would produce.

Yes, this project requires film more than any of my other projects, because the demise of industry in Rochester, NY is what has led to the current economic conditions of Rochester. The reduction in the blue-collar workforce by Kodak, Xerox, Bausch & Lomb, and others has hit Rochester hard, just as in the rest of the Rust Belt. Therefore, this body of work parallels my other work, which is about sociology and economics, while also bringing the history aspect into the work. In the past two years, I have really started to see the connection between this project and PRIVATE | Now Back Go : Go Back | PRIVATE, which has allowed me to understand my underlying influence to my photographs. I think that understanding has allowed my visualization and concept to move to a new level of maturity in my work.

MK: What theme or concept is it that you feel is represented most significantly in your photographs?

EK: I only recently realized that a lot of my work is centered on societal awareness that is often due to my reaction to a situation in my life. Essentially, I am documenting my life and how I have witnessed technology and societal influences become the reasons we are falling apart as a society, which is forcing classifications of everything. Each stage of my life has led to a body of work, which has then allowed me to have a greater awareness to the people I associate with and my surroundings. In return, each body of work has shaped me as the person I am today and the person I hope to help my children into becoming. Therefore, I believe this is why a few curators have labeled me as a “reactionary romantic photographer”. I have actually learned to appreciate this label as one curator explained to me that they could clearly see my emotional presence in the images I create. I clearly am not a true conceptual photographer.

An image from Eric Kunsman’s series Private

An image from Eric Kunsman’s series Private

MK: While documenting the loss of segments of our society to technology, you have at the same time embraced it yourself. You also operate a business that does digital printmaking and book making. How has your background in the analog world of photography informed this part of the business? Do you feel it was necessary to have the traditional skills before taking on this latest direction?

EK: I whole heartedly believe that the traditional skills were necessary before utilizing the various digital printing technology offered to my clients and used for creating my work. Analog helped me to create my skill set that I have today and the understanding of the fine print, along with understanding the language of photography. It was so important to me that when I was still in New Jersey working at the community college, I started a Kodak collection to help people understand when they walk into my studio that I am not just a “Pixel Pusher”, but instead a photographer with the traditional training and love for capturing light. Yes, I prefer film, but in the end, we are simply capturing light. To this day my Kodak collection continues to grow and is yet another hobby of mine.

The name of my studio actually comes from Dan Larkin, a fellow professor at RIT, because when I first started teaching at RIT I was 23, and he used to call me Booksmart Boy, and whenever a faculty needed help with digital printing, I became the “go to” person. So naturally, when trying to decide on a studio name he suggested Booksmart Studio. The name really encompasses the digital printing, non-silver printing, workshops, and hand bookbinding we produce in-house. I am able to develop all of my film in-house, as well in our darkroom where I am able to use a barrage of Jobo’s to expedite the process. The experience of the traditional darkroom and continuation of using film has helped to further my requirement to control all aspects of my process. The digital printing aspect I believe is just another tool for me where I have the same controls for visualization that both film and non-silver printing offer.

I truly prefer to think of myself as a photographer using digital printing techniques as a tool, and not a digital printer taking photographs.

An image from Eric Kunsman’s series Private

MK: I find it quite noteworthy that you also spend some of your time as an educator and lecturer. Is there a part of your teaching that exercises the practice of using analog processes? Do you think that it’s necessary for beginning photographers to have a full grasp of these methods in order to fully grasp the principles of their craft?

EK: Unfortunately, I do not even get to teach photography as an art form, and I believe that is why I do not burn out from creating my own work. Instead, I teach the upper level courses such as Color Management, The Fine Print Workflow, Portfolio Development, & Publication Design. In the Fine Print Workflow class, I do approach the information provided as the Digital Darkroom, meaning that there is a lot of critique of the physical print and the viewers emotion towards it, as was offered in a darkroom class. Students often show up expecting the course to be all “pixel pushing” and are very intrigued on the first day when I explain they need to understand how to see a print and allow it to express what they are trying to emulate to the viewer. I have actually had students drop out of the course after hearing the critique aspect to a printing course.

I personally feel that the emulation of your intent was always lesson #1, along with print critique, in the analog world, and has been often lost in the digital world. I find, too often the students rush through the visualization process, whether during the capture stage or the final output. I truly feel that a photographer with an analog foundation ends up being a stronger visualizer of the final intent. In my opinion, too often photographers are rushing to the conceptual aspect of photography without understanding the craft or technical aspect of photography, which could only help their conceptual ideas.

As I stated previously, my visualization is helped by working with analog and being forced to reflect on an image/scene that is not thrown onto the LCD display on the back of my camera. Thus, allowing me to make sure the final image is a reflection of what I visualized prior to the capture. There were times where I failed miserably, but that is where I learned more which prepared me for later image making. Again, I feel that digital has created a scenario where my students are often scared to fail. The students think that the image they have captured is a representation of their emotional attachment which initially lead them to fire the shutter. An analog photographer understands failure is part of the process and that we often need to perfect our visualization. After all, we are only recording the light that we present to either the analog film or digital sensor, and ultimately, we need to visualize and sculpt that light.

MK: One last thing - we’d love to know what more we might expect to see from you in both the near future and in your long range plans. Anything new we should be on the lookout for?

EK: Currently, my two projects Felicific Calculus and PRIVATE | Now Back Go : Go Back | PRIVATE are ongoing projects. I plan on photographing the PRIVATE | Now Back Go : Go Back | PRIVATE for the foreseeable future, whereas the Felicific Calculus has an end date of Spring 2021, as it will be featured throughout the four floors of exhibition space at CEPA Gallery in Buffalo, NY. During that exhibition we are planning on the traditional photographic print exhibition along with installations and a few community involved documentary projects in the Buffalo area. My only other interest that is starting to percolate is the idea of shooting portraits of the individuals and families that live within half a mile of my studio and their home environment. Otherwise, my next projects will just be a reaction to some influence in my life.

Gallery

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael Kirchoff is a photographic artist, independent curator and juror, and advocate for the photographic arts. He has been a juror for Photolucida’s Critical Mass, and has reviewed portfolios for the Los Angeles Center of Photography’s Exposure Reviews and CENTER’s Review Santa Fe. Michael has been a contributing writer for Lenscratch, Light Leaked, and Don’t Take Pictures magazine. In addition, he spent ten years (2006-2016) on the Board of the American Photographic Artists in Los Angeles (APA/LA), producing artist lectures, as well as business and inspirational events for the community. Currently, he is also Editor-in-Chief at Analog Forever magazine, and is the Founding Editor for the online photographer interview website, Catalyst: Interviews. Previously, Michael spent over four years as Editor at BLUR magazine. Connect with Michael on his Website and Instagram!