Interview: Fred Lyon - 75 Years of Photography

A portion of this Interview by Niniane Kelley was originally published in Edition 1 of Analog Forever Magazine, late 2019.

“...it was the 60s and I was going to New York to do some work in the Life studio and at that same time Look was coming out here and needed a studio for Irving Penn to work in, so they rented my place in Sausalito. Somehow they had convinced the Hells Angels to come in for a photoshoot. They all drove their motorcycles into the freight elevator and up to the second floor where Penn had a big concrete sweep built.

I had stocked the fridge with a lot of beer for Penn, and so the first thing they did was drink all the beer. Some of the Angels' girlfriends were there and in the model's dressing room they discovered a bunch of colored wigs, so they took those with them. They took the sunglasses right off the face of the Look editor. They took a painting that I had bought from a local artist that I had hanging in the kitchen. And I had 50 feet of windows on the second floor and all the Hells Angels lined up and peed in unison out the window. A spectacular thing that should have been recorded. No retakes on that one...”

-Fred Lyon

I was sitting in Fred Lyon's studio on the ground floor of the San Francisco home he shares with his wife Penny, just a few blocks from the bay and practically within touching distance of the Golden Gate bridge. The all-white studio fills with soft light filtering in from the back garden and the sounds of Sonny Rollins and Louis Armstrong play in the background. Fred tells me story after outrageous story and I can do little more than chuckle and shake my head at his many adventures.

I've had the privilege of knowing Fred Lyon for over a decade now. We met when I was a young-ish gallery worker and he was a “spry octogenarian.” A reporter at the time referred to him as such and the phrase caused Fred to grumble and groan over such a characterization, although his complaining was accompanied by a sardonic twinkle in his eyes. I prefer to refer to him as The Most Charming Man In San Francisco. And charming he is, with a disarming nature, a sly sense of humor, and a boundless energy for life and its pleasures.

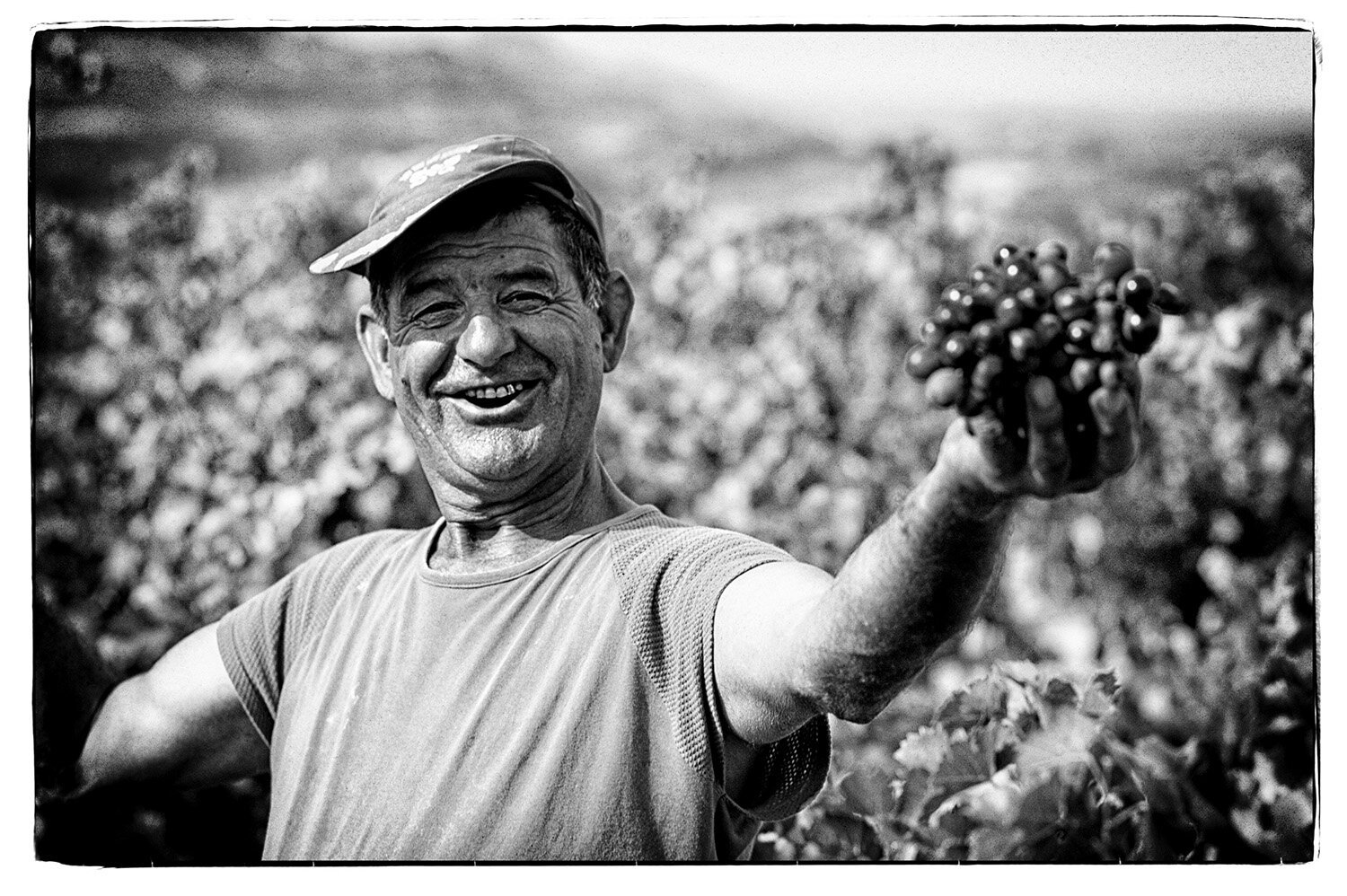

A fourth-generation San Franciscan, Fred Lyon has been photographing his hometown for nearly eighty years and has published three monographs showing life in San Francisco from the 40s through the 60s including San Francisco, Portrait of a City: 1940-1960, and San Francisco Noir. He's also traveled the world photographing for publications such as Life, Vogue, Home & Garden, and Glamour. This fall sees the release of his latest book, Vineyards, published by Princeton Architectural Press.

INTERVIEW

Fred Lyon: You know, at this point in my life I should be sitting in a rocking chair. Some things just don't work out.

Niniane Kelley: I don't think you're made for sitting in a rocking chair.

FL: I think I would be bored out of my mind, but I'd like to try it.

NK: Let's start at the beginning. Tell us about how you got into photography in the first place?

FL: It was very simple. You know, way back then, hobbies were different, and I took up the thing that had the funniest gadgets, which was building radios. Radios had tubes that glowed. And as you have found out, they feel that tube amps have the best sound. Well, my father spoke to me at one point when I was in high school and he said, “This has been a nice hobby. You've made all these radios, but I do have to point out that none of them have ever worked. I was wondering if you could find a slightly less expensive hobby.” And I, being a very flexible and agreeable chap (or feeling pressure from my father) said, “Oh yes, I have a friend who has a camera.” A camera was a shiny and attractive object, and I didn't mention that he also seemed to always have a gaggle of wonderful looking young ladies hanging around him, and I thought, well, maybe if I get a camera...it was a no brainer. I could develop all our film and save him money! Well, nothing ever cost my father more money.

I did get my father to finance my first camera which was a 2 ¼ square single-lens reflex that looked like a precursor of a Hasselblad. It was called a Pilot Super, it was a pot-metal miracle that cost $36. (The Pilot Super was made in Dresden, Germany from 1939-1941). My father fronted me the $36, but I had to work it off by doing garden work. But I did get hooked on it and by that time, I was ready to escape from high school. I was really bored with high school, it was holding back my photography.

By mistake, I weaseled my way in as an assistant at Moulin, the only big commercial studio in San Francisco. At that time it was run by the sons of Gabriel Moulin and they were both terrors, one a little worse than the other. But Moulin Studios was a training source for a whole generation of commercial photographers. Most of everything there was 8x10. It was a tough start, but I was very determined and youthfully, blissfully ignorant, and I stuck with it. When the brothers retired it was sold to camera repairman Adolph Gasser. If those walls could talk we'd have to leave town.

Eventually, I discovered there was a school in Los Angeles called Art Center and I talked them into sponsoring my adventures there. The school was not as enthusiastic as I was, they never had anybody that young, I was 15 or 16, I think. All the students had given something up to go there and they were all older than I. But, you know, Youth! Ignorance! It was marvelous! And so I just threw myself into it and kept lurching forward ever after.

NK: And for 80 years you really never looked back! But, in the meantime, you ended up in the Navy next?

FL: Yes, unfortunately after less than two years at the Art Center we had a war and I was called up to save the world from itself. I went into the Navy because I didn't want to get stuck away in the Army, and I got into the aviation division. The taxpayers are probably still paying for my flight education, but I have never been at the controls of a plane since I left there. It was a marriage of convenience, as soon as the child was old enough to know, we had a divorce.

When I finally got out of the Navy, I had been doing photography for the Navy Press in Washington DC. I had some mustering out pay, so when I got discharged I got on the train and went to New York to have a ritual drunk. After a few days there I got tired of that and people kept saying, “Well what are you going to do now?” It's a little embarrassing to say I've never thought about it!

I think I was 21 then, but just barely. Two people I knew gave me little slips of paper, “Here's someone that has something to do with photography, I'm not quite sure what it is.” I went to see both of them and one place was an enormous old Park Avenue mansion without any signs outside. I kept checking the address, is this the place? I guess I have an appointment here? I finally went inside and an intimidating woman showed me into the office and the next thing I knew I was working for Wilcox Studio.

NK: So basically you went straight from the Navy to being a New York fashion photographer.

FL: I wasn't very good at it. Penn and Avedon weren't worried, and I knew both of them. But the models were fantastic, they had worked for all the great photographers and would help me out. There was this one scrawny girl, she was one of Avedon's early models, and I kept booking her for jobs. I thought she was great, but I knew she would go out to dinner with millionaires and I was too shy to do anything about it. Years later her mother told me the girl said to her, “I know he likes me, why doesn't he do something about it already!” Eventually, we got married, so it all worked out. We had a big wedding in New York in 1951, the guest list was all photographers and editors from fashion and magazines.

The first darkroom man I had there was a very serious man who was much older than I. After I had been there about a month he presented himself to me and said: “I've been making a survey of all your exposures and I find that they fall into different categories.” I said, “Yes, yes!?” he says “Yes, there is underexposure, overexposure, double exposure and no exposure at all!” He wasn't with me for very long. I did not like his attitude. But at that time we hadn't even gotten the first Weston exposure meter. Up until then you just had to know what the exposure was, and bracket to be safe. But this period taught me three important things: play it safe; treat your clients very well; and wear comfortable shoes at all costs.

NK: You moved back to The Bay at the end of the 40s and established your own studio. By that point you were shooting more than just fashion, you were doing editorial, food, travel, a little bit of everything.

FL: I have photographed everything except combat, and I don't feel bad about that because I still have arms and legs. But I have aerials and underwaters, sports, did a million architectural things and interiors, like I did pretty good coverage of the old Fox movie theater before they replaced it, both interiors and exteriors.

NK: And this was the time period when you photographed the San Francisco work that has gotten so much attention recently. Even though we're now viewing these images through the lens of “Art” a lot of this work was shot for commercial assignments, right?

FL: Exactly. I'd call New York and try to sell a story on San Francisco and there'd be young picture editors asking, “Well, what do you got out there?” “Oh, we've got cable cars and steep hills and fog and Chinatown and Herb Caen.” And they'd say, ok, I guess you can do a story for us. So I'd call Herb and say, “Ok Herb, we've got to do it again!” He was a staple.

Herb was marvelous, he's someone I really miss. But, of course, he was one of a kind. He was one of the last really witty people that I knew in this town. I knew him all the time that he was in San Francisco. We weren't really tight buddies like he was with some of his other friends but we were constantly in each other's lives. And I liked going around with him because he knew everybody, which was marvelous. There were a number of people who loved to have fun along with doing real work, and he was one of them. We both had a taste for jazz, and there was a fantastic jazz scene in the Fillmore district at that time. The music was just terrific; the drinks were awful.

NK: One big thing we have in San Francisco is the Golden Gate Bridge, which you've photographed every which way over the years. Some of the most amazing shots are from when you did a story on the bridge painters. How did that come about?

FL: Ah, the end of the month was coming, and at the end of the month I became very industrious because the rent was due. I was living in Sausalito at the time and was constantly driving over the bridge into the city and would see the men out there working. It was fascinating; they start painting at one end of the bridge, get all the way to the other end, and then start all over. They never stop painting. So I thought maybe there's something there and convinced one of my editors it would be a good story. One day I drove up to the office and said, “I'm a photographer and this magazine would like to do a story on the bridge painters.” The man in the office said, “Go out and see Joe, he's the foreman, he'll fix you up.” Joe thought it was really funny, so I got to run around the bridge for a couple of weeks, and the guys saw me running around and a couple of times they saved me from doing something dangerous.

There's a tiny elevator in each tower that is just big enough to fit two people inside. They also discovered they could carry two guys on top of the cage as long as they remembered to stop the elevator in time. Well, the first time I got up to the top I was so excited to have these great viewpoints I started to run down a cable. And one of the guys said, “Hey, buddy I think you better come back here, I want to give you a safety belt.” I really appreciated their concern.

NK: What cameras were you using back then?

FL: Well, the earliest stuff is done on a Rolleiflex. There was a time when I had two, three Rollei’s hanging around my neck at once, and they were banging together and it was terrible! Then we got the Hasselblads with interchangeable backs, then we could change film easily and switch between black and white and color.

I just wish that I had at some time photographed all the cameras I've had. I owned some of the most exotic pieces of photo equipment you could possibly imagine. I also wish I've photographed every automobile I've ever owned, there were times when automobiles were the biggest thing in my life.

NK: You do have that great shot of your wife Anne getting into one of your cars on Nob Hill. I'm rather fond of that one as I live right by there and walk by that street all the time.

FL: That was my Riley. My racing green Riley, even the leather was racing green. That was the time I was into automobiles, and at that time one did not drive Detroit iron at all. I remember when I had to get a terrible old station wagon that I needed to haul lighting gear around in, and I remember one of my friends looked at it and said, that's not a British car!

The thing about the Riley was the frame was wood, and one had to tighten the body bolts on it. We still had some streets that had exposed cobblestones and everything shook, so every couple of months we had to tighten them all up again. It was a real drag, but I was very young and tightening body bolts had caché. It was a good car. I don't know why I finally sold it, I think I sold it for $500.

NK: Even though you were settled in San Francisco you were also taking assignments that took you all over the world...

FL: I had a lot of travel that Time-Life paid for when I was working on their books. In those days with the Time-Life expense account, one could carve a very wide swath in Europe, and even out in the Pacific. So I'm glad I did that then because Time-Life is gone... How lucky I was, I just kind of backed into it. Good timing! I've been Mr. Lucky.

You know, any place that you keep coming back to, it kind of becomes home. Not only was New York home, and also LA, but Paris was home. London never quite made it, but Vienna was home because I worked out of there a lot. In Italy I was always on the move; I had a lot of adventures in Rome but it never became home. But Paris, always. Paris is so big on photography you can't believe it. I was always there at least once a year but now I'm an antique and I don't travel as much, and I don't dance as much, either. Some unwary publisher is going to publish my snaps of fifty years of Paris. He doesn't know it yet, but he will.

But there are a lot of things that didn't pan out, you know. I've had three or four stories that would have taken me to China, but I'd turned them down so I've never been to China. But I've been sent to cover the most incredible things and I've met the most incredible people. I've risked my life, and when it was over, just on adrenaline, I went, “Fred, why did you do that! You're not being paid enough to die!”

NK: What was your most dangerous assignment? Besides the time you almost ran off the top of Golden Gate Bridge.

FL: I don't know, there were so many times I came close to dying, usually involving fast-moving boats. Once when I was in the wrong boots, I was up in Canada on my way to the Arctic Circle and there was an archaeologist there who wanted to show me something that involved climbing up the face of a cliff. I got spread-eagled up on the face of the cliff and I could not move up, down, or back. I was clinging to the side of this cliff with my fingertips and I thought, “Fred, you are such a stupid ass to get yourself in this kind of position!” I didn't have to be there. Ah, Youth!

NK: People nowadays are mostly familiar with your black and white work, but you shot in color as well...

FL: Early on there were not many photographers who were skilled at shooting in color because most of the work up until then had only been black and white. Happily, I had been doing color since before I went in the Navy. At the end of my life in the Navy, there was nothing to photograph but guys getting medals pinned on them, handshake pictures, and I discovered a lot of 4x5 Kodachrome down in our storeroom. Nobody knew what to do with it, so I just kept shooting it and shooting it and getting comfortable with color and the kind of lighting it needed. I really had a jump on a lot of photographers, even working photographers, because I was unafraid to light things. When I was working under contract at Time-Life, I did retakes for some of their biggest name staffers who just did natural light. Sometimes there comes a place where natural light just isn't enough to tell a particular story. And there are other people that only light everything, and I don't believe in that, I love natural light.

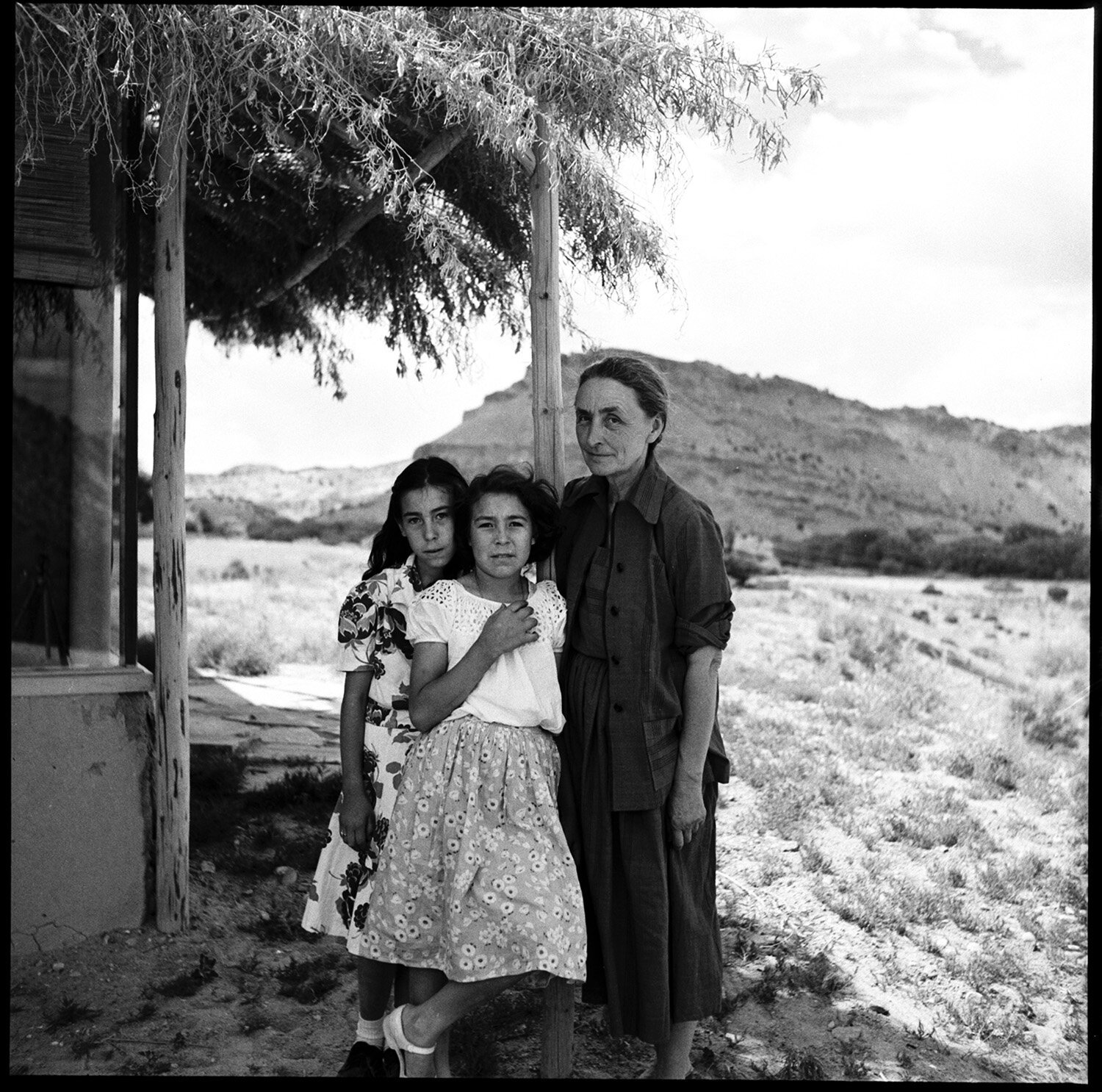

One time I was shooting for Holiday and they were coming out with an issue on New Mexico, and the editors of Holiday were very indulgent. They were self-indulgent and they were indulgent with their little club of what they considered their favorite photographers—and somehow I weaseled in on the tail-end of that group—and not everybody was able to do color well. The color work that the magazine was publishing was terrible. I found an old tear-sheet of part of that story; the paper was awful, the reproduction was terrible, it looks like it was printed on a piece of bread. But when you're on assignment it was important to play it safe and so they asked you to shoot black and white right along with color. That was always a terrible idea because you got the right picture on the wrong film. I eventually got to a place where I would say “No, I don't do that, it's one or the other” and everybody wanted color.

NK: This was the assignment where you photographed Georgia O'Keefe?

FL: Exactly. But we had never looked at the black and white film because the color was so good! Recently I went back to it because I knew that I had a couple of good pictures of her in the files and when I started to look through it, Laurel, who works for me, said, “Oh, what about this, what about that!” So we printed up a whole portfolio, some of which now hangs in O'Keefe's house in Santa Fe. But I started looking at it again the other day and said, we've got to finish looking through these black and whites. I don't know that it's a book, and, of course, no place has more photographers than Santa Fe, but somebody might want to do something. I at least want to get that body of work together, because if we don't make some effort at this point, later on, nobody else will.

NK: You have a massive archive here in the studio, filing cabinets and boxes and flat files full of work, but you don't have everything. For assignments you've done on contract for magazines, how did that work?

FL: The way we used to work was: I would shoot something for Life and I would have to take the film and put it in a big red envelope and take it down to the airport. At that time there was something called Air Express. The big red envelopes were easy to spot on the other end and there was always somebody waiting for the film. They would take it to the lab and I would never see the pictures again. And when I think of all the things that could be in my file... I've photographed five presidents and I don't think I have anything from those. There was a fashion story on Reagan's wife, I may have a few of those. Legally I was supposed to have a certain amount of access and a few times I've been able to retrieve something from the library, but now a lot of it is at Getty and so it's not worth the trouble.

Besides, I have too many pictures already, what am I going to do with these? Things are pretty well organized, but nothing is ever well organized enough. I am viewing photography a little bit differently these days. I don't get to shoot anymore because I can't run around up and down mountains, and so I'm mostly working in my library. It's really interesting because what I have is work that I didn't have time to edit that I stuffed in the files. Now when I go back I have learned to look at it with a more educated eye. And there are a couple of other projects I have in mind, we have what Penny calls “Fred's Faves” and nobody is ever going to do anything with those. I'm stubborn, if there's something I really like I don't throw it away. And some of them are looking better and better than they did originally at this point. I have a couple of moments where I have to say, “Gee Fred, you weren't so bad after all, in spite of what everybody said.” But I'm of interest to historians. I'm a great success with small children and old ladies and dogs. They don't all follow me around, but they accept me.

NK: Well, you certainly have enough material to keep making books. Your new book on wine will be out this fall, right?

FL: With this new book I realized that if I was going to do it, I had to do it now. Because I could put together the hot team, and, as you've discovered, there's very little we can do by ourselves. I was afraid that the team was so hot that it wouldn't be together forever. It's the only reason I agreed to do it, because this book is covering thousands and thousands of wine and vineyard pictures from all over the world, from as early as 1947. I knew this team had the talent to pull it off. The book designer who did my last book is a young energetic genius and he manages to pick the pictures that I love, and he is so good at laying them out and sequencing them. So I rattled his cage and he came up with a first take and I loved what he did with it. It isn't what I would have done at all, it's much, much better.

In the creative world, old projects tend to get nibbled and if you have a hot idea and you believe in it, grab it now and shake the hell out of it. Get it by both lapels, or even by the ears, and insist. I guess that's what painters call passion. I've known some really good people I was very fond of and I admired, and they kept getting ready, and then kept getting ready, but they came and they went and they were still getting ready. I don't offer advice on that basis because there are a lot of people who plunge forward without any effort at being prepared.

NK: Any final thoughts before Penny comes down and kicks me out for staying too long?

FL: My advice to everybody: if you want to have fame, you just have to live forever and it will find you. I'm not saying that's a good thing, it's just the way things are.

This is my 94th, soon to be my 95th year, and I used to think that anybody over 30 would want to be put out of their misery. Why would they want to hang around after the party was over? I don't feel like that anymore, I'm having such a good time that I don't want to check out. I'd like to start all over again if I had the time. I just need another hundred years, I'll settle for that. And while the machinery doesn't work anymore, once in a while I get a really good flash. My buddy Penny is a miracle. I've ruined her life, but I'm not letting her free at this point. And she has the most incredible sense of humor and we share a sense of the absurd and it's marvelous, so I don't want to miss that.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Niniane Kelley is a fine art photographer living and working in San Francisco and Lake County, California. A native of the Bay Area, she is a San Jose State University graduate, earning a BFA in Photography in 2008.

Drawn to photography for both the immediacy of the image making process and the intrinsic alchemy of the darkroom ritual, she crafts the majority of her imagery using traditional 19th century processes which give each piece its own unique character.

She teaches workshops in the Bay Area and surrounding environs. She most recently worked as a photographer and manager at San Francisco’s tintype portrait studio, Photobooth.

Connect with Niniane Kelley on her Website and on Instagram!

In This Room Will Survive Me, Cindy Konits uses afternoon light, architecture, and expired instant film to examine interiority as something formed in the rooms we inhabit. Through long, uncertain exposures and chance-driven chemistry, her images merge body, space, and memory into scenes that feel lived rather than observed. The work leaves a quiet proposition: our inner lives are shaped in thresholds, light, and time, and rooms continue to shape us long after we’re gone.